Heat Treating of Tin-Rich Alloys

Abstract

In heat treating of tin-rich alloys, it is difficult to secure an effective and permanent degree of hardening. Tin melts at 232°C (505 K), and therefore room temperature (about 295 K) is well over one-half the absolute melting point. It follows that high-temperature behavior such as recrystallization and recovery can occur in fairly short times, even at room temperature. Tin is also an unusual metal because it can work soften under certain conditions, and so heat treating can be used in these cases to restore some of the original hardness and strength.

In heat treating of tin-rich alloys, it is difficult to secure an effective and permanent degree of hardening. Tin melts at 232°C (505 K), and therefore room temperature (about 295 K) is well over one-half the absolute melting point. It follows that high-temperature behavior such as recrystallization and recovery can occur in fairly short times, even at room temperature. Tin is also an unusual metal because it can work soften under certain conditions, and so heat treating can be used in these cases to restore some of the original hardness and strength.

Heat treating of tin-rich alloys has been practiced for bearing alloys, pewter ware and organ pipe alloys. Some of the principles underlying these applications will be reviewed first.

Binary Alloys

Tin-antimony, tin-bismuth, tin-lead, and tin-silver alloys can all be temper hardened by solution treatment and aging. However, only the tin-antimony alloys can be permanently strengthened by heat treatment; all other tin-rich binary alloys will gradually soften at room temperature.The greatest improvement obtainable in binary tin-antimony alloys occurs in the alloy that contains 9% Sb; a hardness of 21 HB and a tensile strength of 51 MPa (7.4 ksi) can be increased to 26 HB and 65 MPa (9.4 ksi). This alloy is tempered for 48 h at 100°C (212°F) after being quenched from 225°C (435°F). During this tempering treatment, ductility decreases from 20 to 10% elongation.

Ternary Alloys

Permanent effects produced by heat treatment also carry over into ternary alloys of tin, antimony, and cadmium. This was discovered during an early investigation of the strength and hardness of ternary alloys containing up to 43% Cd and 14% Sb using chill-cast specimens.It was found that the strengthening effect of cadmium in the terminal solution tin phase (alpha) is much greater than that of antimony. In this study, the maximum stable values obtained in alloys containing 7 to 9% Sb and 5 to 7% Cd were as follows: tensile strength 108 MPa (15.7 ksi), elongation 15%, and hardness 35 HB. The presence of the sigma phase (principally SbSn) as primary cuboids had no effect on strength or hardness, but the presence of primary epsilon (CdSb) destroyed the useful mechanical properties.

Therefore, alloys containing cadmium generally use compositions that restrict the formation of the primary (CdSb) epsilon phase. The maximum combination of strength, ductility, and hardness is obtained in alloys that have finely dispersed precipitates of the sigma and epsilon phases in an alpha matrix, or finely dispersed epsilon in a matrix of alpha with a eutectoid of (α + γ). These structures are typically achieved by quenching or rapid cooling from elevated temperatures to avoid precipitation of primary sigma and epsilon.

Additional heat-treatment studies have been directed to a group of cold-workable tin-rich alloys containing 3 to 8% Cd and 1 to 9% Sb. Two forms of hardening were observed on quenching of these alloys from 185 to 200°C (365 to 390°F). One form results from the change in solubility of antimony in tin or in the beta phase. The other, which produces more intensive hardening, is analogous to hardening of binary cadmium-tin alloys by quenching and depends on suppression of eutectoid decomposition of the beta phase. Permanent improvement results in the first instance. Therefore, a maximum tensile strength of 101 MPa (14.6 ksi) was achieved in a Sn-3Cd-7Sb alloy that was quenched from 190°C (375°F) and then aged for either 24 h at 100°C or 18 months at room temperature.

Further studies have been carried out on tin-base alloys containing 7 to 10% Sb and 0 to 3% Cd in an effort to locate a bearing alloy that would be suitable at mildly elevated temperatures. In this composition range, it was found that alloys containing 0.5 to 2% Cd (but not 3%) can be strengthened considerably by quenching and tempering.

Optimum properties (tensile strength 92 Mpa) were obtained in a Sn-9Sb-1.5Cd alloy quenched from 220°C (430°F) and then aged for 1000 h at 140°C. This alloy consists of finely divided sigma and epsilon phases in a matrix of alpha.

Pewter

Many pewter articles are manufactured from sheet prepared by cold reduction of cast bars or slabs. Tin-rich pewter alloys containing antimony and copper will work harden during sheet-rolling operations that involve small percentage reductions (20%). If left standing at room temperature, the alloy will recrysiallize and soften until it has reverted to the hardness of the original cast bar or slab. On the other hand, if large reductions (such as 90%) are made and the crystals are heavily worked, the alloy will work soften. Then, as crystals increase in size, hardness increases slightly, but never to the level of the original cast material.The hardness values of spun pewter ware, or of other articles that have been manufactured by mechanically working the metal, can be restored by heat treatment at temperatures from 110 to 150°C. A tin alloy containing 6% Sb and 2% Cu hardens to 90% of the hardness of the as-cast material after annealing for 1 h at 200 °C. Longer annealing times at lower temperatures have smaller but similar effects on the recovery from work softening.

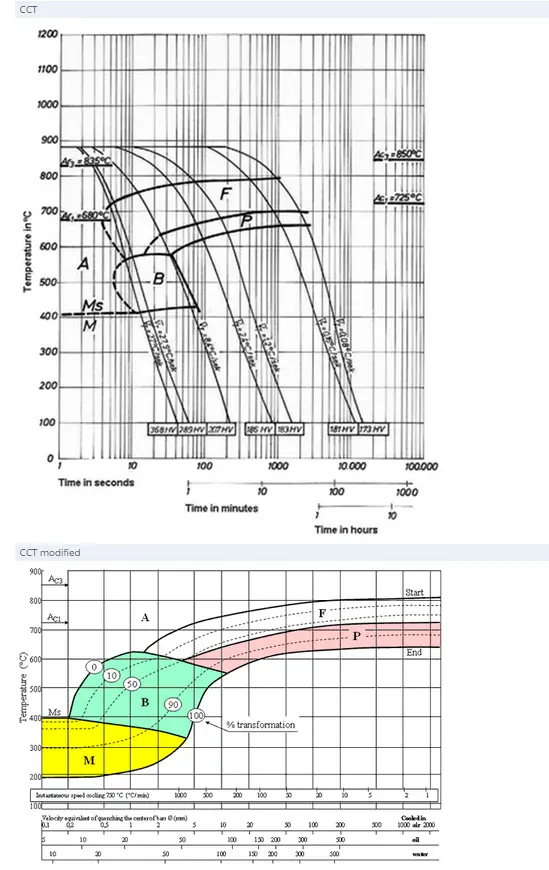

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.