Bainitic Steels: Part One

Abstract

The region in which lath-shaped fine aggregates of ferrite and cementite are formed, which possess some of the properties of the high temperature reactions involving ferrite and pearlite as well as some of the characteristics of the martensite reaction.

The generic term for these intermediate structures is bainite after Edgar Bain who with Davenport first found them during their pioneer systematic studies of the isothermal decomposition of austenite. Bainite also occurs during thermal treatments at cooling rates too fast for pearlite to form, yet not rapid enough to produce martensite. The nature of bainite changes as the transformation temperature is lowered. Two main forms can be identified, upper and lower.

The Bainite Reaction

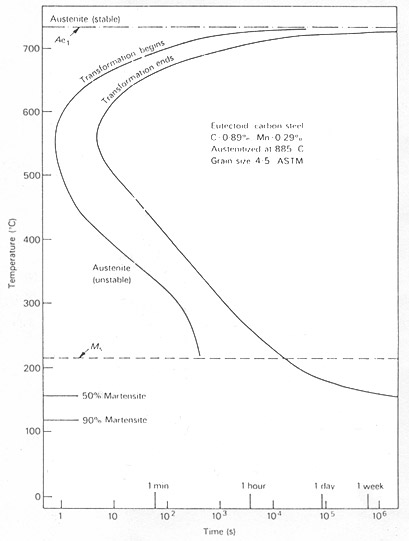

Examination of the TTT diagram for a eutectoid carbon steel, Fig. 1, bearing in mind the fact that the pearlite reaction is essentially a high temperature one occurring between 550°C and 720°C and that the formation of martensite is a low temperature reaction, reveals that there is a wide range temperature, usually 250-550°C, when neither of these phases forms.

Fig.1: Time-Temperature-Transformation (TTT) diagram for a 0.89 carbon steel

(US Steel Co., Atlas of Isothermal Diagrams)

This is the region in which lath-shaped fine aggregates of ferrite and cementite are formed, which possess some of the properties of the high temperature reactions involving ferrite and pearlite as well as some of the characteristics of the martensite reaction.

The generic term for these intermediate structures is bainite after Edgar Bain who with Davenport first found them during their pioneer systematic studies of the isothermal decomposition of austenite. Bainite also occurs during thermal treatments at cooling rates too fast for pearlite to form, yet not rapid enough to produce martensite. The nature of bainite changes as the transformation temperature is lowered. Two main forms can be identified, upper and lower.

Morphology and Crystallography of Upper Bainite

The morphology of upper bainite (temperature range 550-400°C) bears a close resemblance to Widmanstätten ferrite, as it is composed of long ferrite laths free from internal precipitation.

Two-surface optical micrography decisively reveals that the ferrite component of upper bainite is composed of groups of thin parallel laths with a well-defined crystallographic habit. Like Widmanstätten ferrite, the bainitic ferrite laths exhibit the Kurdjumov-Sachs relationship with the parent austenite, but the relationship is less precise as the transformation temperature is lowered.

A widely-accepted view is that the crystallography of upper bainite is very similar to that of low-carbon lath martensite. However, a detailed examination of the crystallography reveals that there are significant differences, and that upper bainite ferrite formation cannot be understood in terms of the crystallographic theory of martensite-formation.

Electron microscopy shows that upper bainite laths have a fine structure comprising smaller laths about 0.5 μm wide. These laths all possess the same variant of the Kurdjumov-Sachs relationship, so they are only slightly disoriented from each other. The longitudinal boundaries are, therefore, low angle boundaries.

A typical austenite grain will have numerous sheaves of bainitic ferrite exhibiting the several variants of the Kurdjumov-Sachs orientation relationship, so large angle boundaries will occur between sheaves. The dislocation density of the laths increases with decreasing transformation temperature, but even at the highest transformation temperatures the density is greater than that in Widmanstätten ferrite.

The upper bainitic ferrite has a much lower carbon concentration (<0.03% C) than the austenite from which it forms, consequently as the bainitic laths grow, the remaining austenite is enriched in carbon. This is an essential feature of upper bainite which forms in the range 550-400°C when the diffusivity of carbon is still high enough to allow partition between ferrite and austenite. Consequently, carbide precipitation does not occur within the laths, but in the austenite at the lath boundaries when a critical carbon concentration is reached.

The morphology of the cementite formed at the lath boundaries is dependent on the carbon content of the steel. In low carbon steels, the carbide will be present as discontinuous stringers and isolated particles along the lath boundaries, while at higher carbon levels the stringers may become continuous. With some steels, the enriched austenite does not precipitate carbide, but remains as a film of retained austenite. Alternatively, on cooling it may transform to high carbon martensite with an adverse effect on the ductility. This type of bainite is often referred to as granular bainite.

Morphology and Crystallography of Lower Bainite

Lower bainite (temperature range 400-250°C) appears more acicular than upper bainite, with more clearly defined individual plates adopting a lenticular habit. Viewed on a single surface they misleadingly suggest an acicular morphology.

However, two-surface optical microscopy of lower bainite indicates that the ferrite plates are much broader than in upper bainite, and closer in morphology to martensite plates. While these plates nucleate at austenitic grain boundaries, there is also much nucleation within the grains, i.e. intragranular nucleation, and secondary plates form from primary plates away from the grain boundaries.

Electron microscopy shows that the plates have a similar lath substructure to upper bainite, with the ferrite subunits about 0.5 μm wide and slightly disoriented from each other. The plates possess a higher dislocation density than upper bainite, but not as dense as in martensites of similar composition.

The crystallography of the plates seems to depend both on the temperature of transformation, and on the carbon content of the steel. Moreover they showed that the phenomenological theory of martensite could be used for lower bainite to give satisfactory agreement between theory and experiment.

Ohmori and coworkers have found that, in a 0.1% C steel, bainite formed near the Ms has a {011}α habit plane and a <111>α growth direction similar in behavior to low carbon lath martensite. However, on increasing the carbon to 0.6-0.8% C, the habit of the bainitic ferrite plates changes to {122}α//{496}γ, which is not the same as for martensite of the same composition which has a {225}γ habit plane. Because of such variations, it has been suggested that lower bainite is not a true martensitic reaction. However, there is no reason to expect the transformations to be identical, and anyway the inhomogeneous shear would be expected to occur by slip in lower bainite, whereas twinning is the mode adopted in higher carbon martensites.

However, in contrast to tempered martensite the cementite particles in lower bainite exhibit only one variant of the orientation relationship, such that they form parallel arrays at about 60° to the axis of the bainite plate. This feature of the precipitate suggests strongly that it has not precipitated within plates supersaturated with respect to carbon, but that it has nucleated at the γ/α interface and grown as the interface has moved forward. It thus appears that the lower bainite reaction is basically an interface-controlled process leading to cementite precipitation, which then decreases the carbon content of the austenite and enhances the driving force for further transformation.

Read more

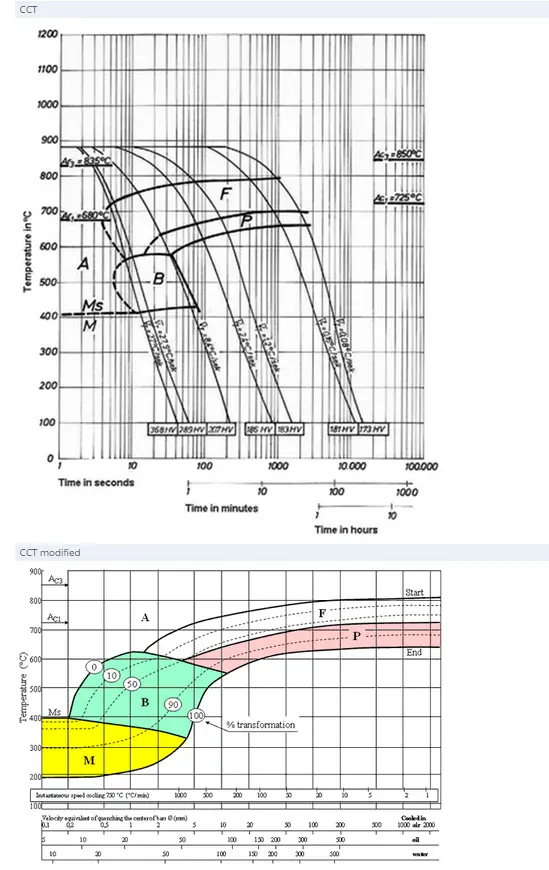

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.