Solid State Welding

Abstract

Solid state welding encompasses various processes that join materials below their melting points without using filler metals. This comprehensive review examines eight major solid state welding techniques: cold welding, diffusion welding, explosion welding, forge welding, friction welding, hot pressure welding, roll welding, and ultrasonic welding. Each process utilizes unique combinations of time, temperature, and pressure to achieve material coalescence while maintaining base metal properties. The article explores the principles, applications, and advantages of each method, with particular emphasis on their industrial applications and capability to join dissimilar metals.

Introduction to Solid State Welding Principles

Solid state welding represents a group of joining processes that produce material coalescence at temperatures below the melting point of the base materials, without the addition of brazing filler metal. These processes may or may not require pressure application and are distinguished from traditional fusion welding methods by their ability to maintain original material properties.

The fundamental advantage of solid state welding lies in its ability to preserve base metal characteristics without creating significant heat-affected zones. This becomes particularly valuable when joining dissimilar metals, where thermal expansion and conductivity differences pose less of a challenge compared to arc welding processes.

Time, temperature, and pressure interact uniquely in each process, with durations ranging from microseconds to hours. As temperature increases, required time typically decreases. Each process demonstrates distinct characteristics and applications, warranting individual examination.

Cold Welding (CW)

Cold welding achieves material coalescence through the application of extreme pressure at room temperature, resulting in substantial deformation at the weld interface. The process requires exceptionally clean interfacing surfaces and high pressure application. While simple hand tools suffice for thin materials, joining heavier sections typically requires press equipment to generate adequate pressure.

The process is particularly effective for joining aluminum and copper, either individually or in combination. Characteristic indentations typically form in the welded parts, serving as visual indicators of weld formation. The process demonstrates particular effectiveness with ductile metals, making it ideal for specific industrial applications.

Diffusion Welding (DFW)

Diffusion welding represents an advanced joining technique that combines pressure and elevated temperatures to achieve coalescence without significant deformation or melting. The process may incorporate filler metals, often in the form of electroplated surfaces, and requires precise temperature control through induction, resistance, or furnace heating.

This process excels in joining refractory metals at temperatures approximately half their melting points, making it invaluable in aerospace applications. Success depends on extremely precise joint preparation and environmental control, typically requiring vacuum or inert atmosphere conditions. The aerospace and aircraft industries extensively utilize this process, particularly for joining dissimilar metals.

Explosion Welding (EXW)

Explosion welding creates joints through controlled detonation, generating high-velocity collision between components. Despite being classified as a solid-state process, temporary interface melting occurs due to impact-generated shock waves, collision energy conversion, and plastic deformation at the interface.

The process creates strong welds between almost all metals, including combinations not feasible with arc processes. Notable applications include metal cladding, heat exchanger fabrication, and tube-to-tubesheet joining. The process maintains the effects of cold work and other mechanical treatments while providing joint strength equal to or greater than the weaker base metal.

Forge Welding (FOW)

This traditional process, historically known as hammer welding, represents one of the oldest welding methods. It involves heating materials in a forge below melting temperature and applying pressure through hammering. While its industrial significance has diminished, the process demonstrates fundamental solid-state joining principles through skilled manipulation to achieve coalescence.

Friction Welding (FRW)

Friction welding produces coalescence through mechanically-induced sliding motion between rubbing surfaces under pressure. The process generates heat through friction, with coalescence occurring when rotation stops and additional pressure is applied. Two primary variations exist: conventional and inertia welding.

In conventional friction welding, one component remains stationary while the other rotates at a constant motor-controlled speed. The parts meet under specific pressure for a predetermined time before rotation ceases and pressure increases to complete the weld. Inertia welding utilizes a flywheel to store rotational energy, which dissipates as heat when the parts contact under pressure.

The process success depends on three critical parameters: rotational speed (determined by material and interface diameter), pressure (varying throughout the welding sequence), and welding time (typically several seconds). Quality assessment often relies on examining the characteristic flash formation around the weld perimeter. The process offers rapid production of high-quality welds without filler metal or flux, though it requires specialized equipment.

Hot Pressure Welding (HPW)

Hot pressure welding combines heat and pressure to achieve coalescence through macro-deformation of the base metal. The process operates in controlled environments, typically using vacuum or shielding media. Surface deformation breaks oxide films, creating clean metal contact points where diffusion occurs across the interface.

The aerospace industry frequently employs this technique, particularly in its hot isostatic pressure variant, which utilizes hot inert gas in pressure vessels. The controlled environment and precise pressure application make it ideal for critical aerospace components where weld integrity is paramount.

Roll Welding (ROW)

Roll welding achieves coalescence through a combination of heating and roll-applied pressure, causing deformation at the faying surfaces. Unlike forge welding, which uses hammer blows, roll welding applies continuous pressure through rolls to create strong diffusion bonds at the interface.

The process finds extensive application in producing clad materials, particularly in joining stainless steel to mild or low-alloy steel. The instrument industry relies heavily on this technique for manufacturing bimetallic materials, where precise control of material properties is essential.

Ultrasonic Welding (USW)

Ultrasonic welding employs high-frequency vibratory energy combined with pressure to create coalescence. A transducer converts electrical energy into mechanical oscillations, applied parallel to the weld interface through specialized tooling. This process creates minute deformations and moderate temperature increases in the weld zone while simultaneously breaking up surface oxides.

The process particularly suits joining thin materials, making it invaluable in electronics, aerospace, and instrument manufacturing. While restricted to relatively thin sections, ultrasonic welding produces joints with strength equivalent to the base metal and successfully joins many dissimilar metal combinations.

Industrial Applications and Quality Control

Each solid state welding process serves specific industrial needs, from aerospace components to electronic assemblies. Quality control methods vary by process but generally include:

- Visual inspection of weld characteristics

- Mechanical testing of joint strength

- Non-destructive testing where applicable

- Process parameter monitoring and control

Conclusion

Solid state welding processes continue to evolve, offering unique solutions for challenging joining applications. Their ability to join dissimilar metals and maintain base material properties makes them invaluable in modern manufacturing. Understanding each process's capabilities and limitations enables engineers to select the most appropriate method for specific applications.

The future of solid state welding lies in automation, process control refinement, and expanding applications in emerging industries. As materials and manufacturing requirements become more complex, these processes will likely play an increasingly important role in industrial production.

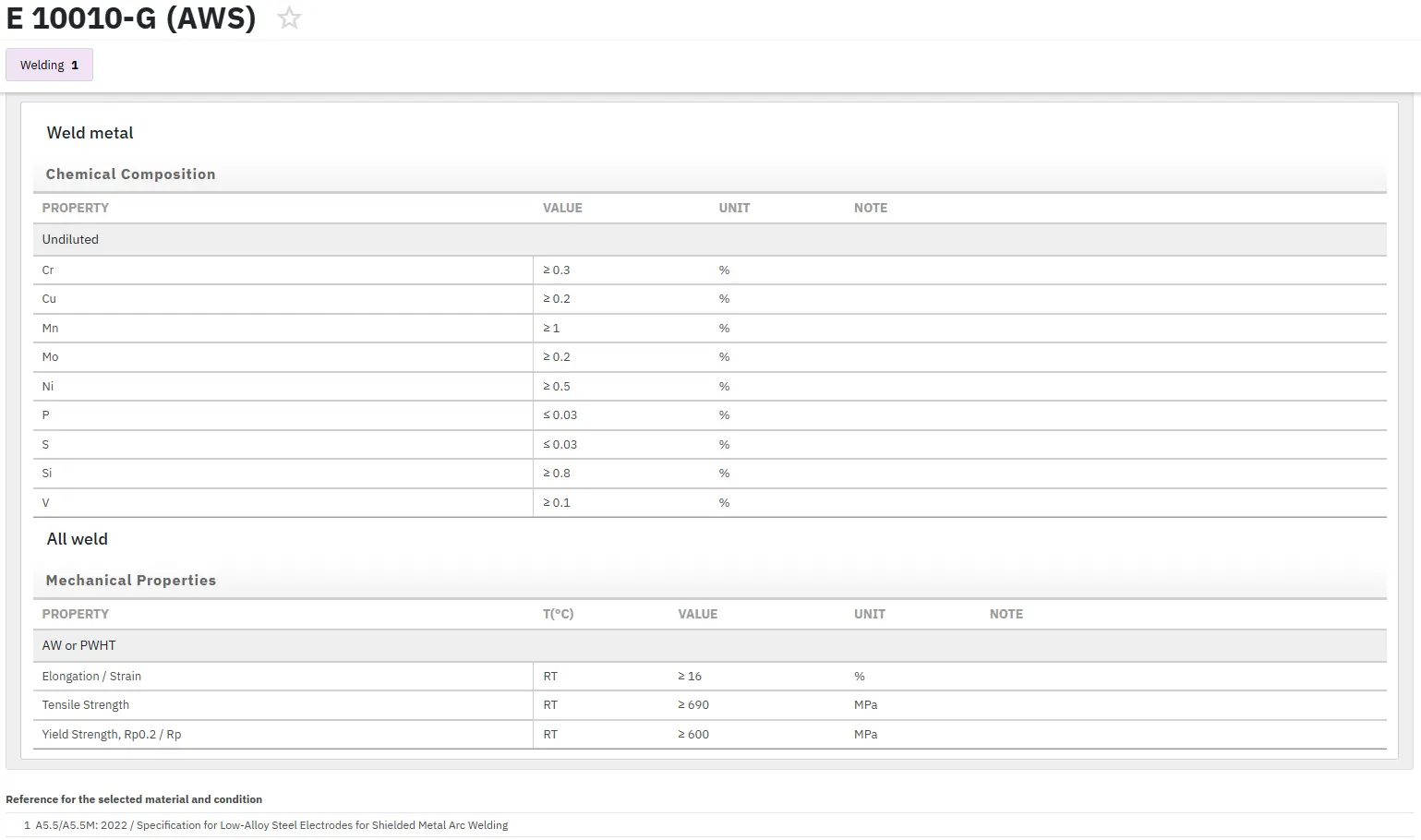

Find Instantly Thousands of Welding Materials!

Total Materia Horizon contains thousands of materials suitable for welding and electrodes, with their properties in bulk and as welded conditions.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.