Hardening of Al-Mg-Cu alloys: Part Two

Abstract

A study of age hardening of three commercial purity Al-Cu-Mg alloys shows that the formation of Cu-Mg clusters coincides with the rapid hardness increase during natural ageing. It is also shown that the yield strength can be accurately described by a model incorporating modulus hardening originating from the difference in modulus between Al and Cu-Mg clusters and solution strengthening.

The second rapid hardening reaction is smaller than the first one and this is likely to be due to the tendency for recovery at the aging temperature. These aging times correspond to: immediately after the rapid hardening, at the end of the hardness plateau and peak hardness, respectively.

Since solutes are uniformly distributed in the matrix after aging for 1 min, the initial rapid hardening cannot be attributed to the homogenous precipitation of GPB zones or to a uniform dispersion of Cu-Mg co-clusters. However, evidence for Cu-Mg co-clusters is observed after 60 min aging at 200°C and GPB zones are clearly observed by the 3DAP after 480 min at 200°C. This indicates that GPB zones are readily detectable by the 3DAP when present in the matrix, and we therefore conclude that there are no GPB zones formed after the initial rapid hardening.

Furthermore, the results indicated that the formation of GPB zones is associated with the onset of the second stage of hardening. The GPB zones observed in these alloys are thought to evolve from the Cu-Mg co-clusters through a continuous growth process similar to that involving Mg-Ag co-clusters observed recently in Al-Cu-Mg-Ag alloys and that involving Mg-Si co-clusters in Al-Mg-Si alloys.

Wilson and Partridge reported that the dislocation loops and helices formed during quench lower the nucleation barrier of the S phase particles and cause the precipitation of the S phase in the early stage of aging. This suggests that solute atoms rapidly diffuse to the dislocations during aging, where nucleation of the S phase occurs rapidly.

Since the dislocations also act as vacancy sinks, the number of the quenched-in vacancies would decrease significantly in the matrix phase, thereby retarding the kinetics of homogeneous or uniform precipitation of GPB zones in the matrix. This would seem to explain the very long incubation period preceding GPB zone formation. It is noteworthy that in many age hardenable aluminum alloys, GP zones usually precipitate spontaneously in uniform dispersions after brief aging treatments.

The retarded kinetics of the zone formation in the present Al-Cu-Mg alloys may be accounted for by the rapid annihilation of the quenched-in vacancies. The existence of the wide PFZ near the heterogeneously nucleated S precipitates indicates a depletion of solute and vacancies near the dislocations and is interpreted as further evidence for a preferred solute-dislocation affinity.

As mentioned above, the 5% deformation on the rapidly hardened specimen caused further rapid hardening at 150°C and this strongly suggests that solute-dislocation interaction is one of the main reasons for the rapid hardening. The occurrence of plastic instabilities in the deformation of Al-Mg alloys is well known to relate to the tendency of Mg atoms to diffuse to dislocations, producing a dynamic strain aging effect.

Recently, Chinh et al. also reported this effect in dilute binary Al-Cu alloys in the as-quenched condition. These results support the proposal that a solute-dislocation interaction can influence significantly the mechanical properties of aluminum alloys.

While the present results indicate that a solute-dislocation interaction causes the first stage of strengthening, rather than a uniform dispersion of Cu-Mg co-clusters, it is also clear that such clusters do form during the later stages of the aging sequence. Moreover, the presence of a uniform dispersion of Cu-Mg co-clusters was detected prior to the observation of GPB zones and it is almost certain that these clusters evolve into GPB zones as they grow in size and increase in order. The formation of these microstructural constituents produces the second stage of hardening.

Room temperature age hardening mechanisms of commercial purity Al-1.2Cu-1.2Mg-0.2Mn and Al-1.9Cu-1.6Mg-0.2Mn (wt%) alloys were studied by hardness testing, DSC, isothermal calorimetry and 3DAP analysis. In the two alloys, hardening at room temperature occurs between about 0.5h and 20h at room temperature, and subsequently hardness remains constant.

3DAP analysis showed that after a short time of natural ageing Cu-rich clusters are present, and on further room temperature ageing Cu-Mg clusters form. During the room temperature hardening, the density of clusters increases and the Cu:Mg ratio in the clusters approaches unity. DSC and isothermal calorimetry shows that the formation of Cu-Mg clusters coincides with a substantial exothermic heat release.

The microstructural analysis shows that the formation of Cu-Mg clusters coincides with the rapid hardness increase during natural ageing. The kinetics of cluster formation is analysed, and the results indicate that, even though the kinetics of Cu-Mg cluster formation will involve detailed 29 atomistic interactions, it can be described well as a classical nucleation and growth process.

It is also shown that the yield strength (converted from hardness data) of these two alloys can be accurately described by a model incorporating modulus hardening originating from the difference in modulus between Al and Cu-Mg clusters and solution strengthening.

The following conclusions have been reached:

- 1. There are no GPB zones formed after the rapid hardening reaction. This rule out the possibility that the initial rapid hardening is originated from the precipitation of GPB zones.

2. No evidence for the presence of solute clusters has been obtained immediately after the rapid hardening reaction. The co-clustering of Cu and Mg was observed towards the end of the hardness plateau and these clusters are thought to evolve into GPB zones during the second stage of the age-hardening process. Thus, the initial rapid hardening is not caused from uniformly dispersed clusters of solute.

3. A further rapid hardening reaction was observed when the rapidly hardened specimen was re-aged after deformation. This indicates that the rapid hardening is related to a solute-dislocation interaction. We propose that solute segregation to the existing dislocations causes dislocation locking due to a solute-dislocation interaction and that this is the origin of the initial rapid hardening.

Read more

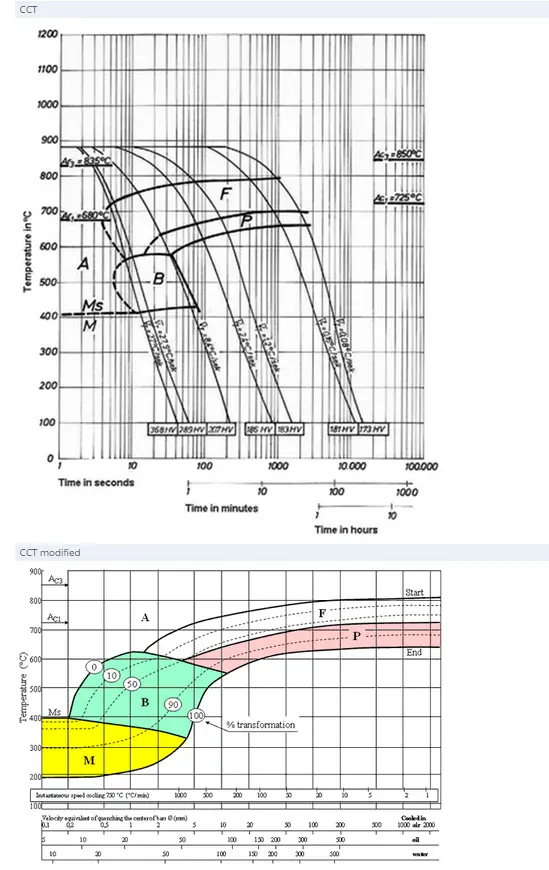

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.