Stress Relief Cracking of Ferritic Steels: Part One

Abstract

Stress-Relief Cracking (SRC), also known by various synonyms, represents intergranular cracking occurring in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) or weld metal during exposure to in-service temperatures or post-weld heat treatments. This phenomenon primarily affects precipitation-strengthened, creep-resistant alloys including ferritic steels, low-alloy structural steels, and austenitic stainless steels. The coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ) demonstrates the highest susceptibility due to its low ductility and microstructural characteristics. Current research suggests that SRC results from impurity segregation, particularly phosphorus, to grain boundary/carbide interfaces or carbide-free grain boundary areas. The cracking mechanism involves carbide precipitation during post-weld heat treatment, creating strong grain interiors while weakening grain boundaries, ultimately leading to strain localization and intergranular failure.

Understanding Stress Relief Cracking in Ferritic Steels

Stress-Relief Cracking (SRC) represents a critical failure mechanism known by multiple designations including strain age-cracking, reheat cracking, stress-assisted grain boundary oxidation (SAGBO), post-weld heat treatment cracking, and stress-induced cracking. This intergranular cracking phenomenon occurs specifically in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) or weld metal when materials experience exposure to in-service temperatures or undergo post-weld heat treatments.

Although the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, the scientific community generally agrees that SRC results from impurity segregation, particularly phosphorus, to grain boundary/carbide interfaces or carbide-free grain boundary regions. This consensus provides the foundation for understanding why certain materials demonstrate higher susceptibility to this failure mode.

Material Susceptibility and Microstructural Factors

Stress relief cracking represents a common cause of weld failures in numerous creep-resistant precipitation-strengthened alloys. The phenomenon occurs exclusively in materials undergoing precipitation hardening, including ferritic creep-resisting steels, low-alloy structural steels, austenitic stainless steels, and specific nickel-based alloys. Notably, plain carbon steels remain immune to stress-relief cracking, though they lack the superior corrosion and creep resistance offered by the susceptible materials.

Research demonstrates that CrMo steels exhibit reheat cracking when chromium content reaches approximately 3wt% or less, although observations have documented occurrences in steels containing higher chromium concentrations. The fracture surfaces typically appear smooth and featureless, occasionally displaying cavitation and localized microvoid coalescence along prior austenite grain boundaries.

Coarse-Grained Heat-Affected Zone Vulnerability

The coarse-grained heat-affected zone (CGHAZ) demonstrates the highest susceptibility to SRC due to its characteristic low ductility, extensive grain growth, and vulnerable microstructure within the weldment. The SRC susceptibility depends heavily on the final microstructure, which the material composition and weld thermal cycle determine.

During the welding process, metal surrounding the weld pool experiences elevated temperatures, triggering significant microstructural changes. The CGHAZ reaches temperatures well within the austenite region, causing carbide dissolution and unrestricted grain growth. Rapid cooling rates maintain alloying elements such as vanadium, molybdenum, and niobium in solution, while austenite transforms into low-ductility, high dislocation density products including bainite and martensite.

Precipitation Mechanisms During Post-Weld Heat Treatment

When materials undergo post-weld heat treatment, alloy carbides precipitate within grain interiors at dislocation jogs and intersections. These submicron precipitates distribute finely throughout the structure, creating considerable strengthening in grain interiors. During tempering or PWHT, carbide precipitation relieves lattice strain from carbon supersaturation.

Research suggests that alloy carbide precipitation, including NbC, Mo2C, and V4C3, counterbalances the tempering effects of Fe3C carbide precipitation during post-weld heat treatment. This precipitation behavior creates a microstructural imbalance between strengthened grain interiors and weakened grain boundaries.

Controlling Factors and Failure Mechanisms

During PWHT, residual stress relief occurs through material plastic deformation. When microstructures develop strong grain interiors resistant to plastic deformation alongside weak grain boundaries, strain localizes at the grain boundaries. The arc welding process elevates base material temperatures near the fusion zone to near-melting points, entering the austenite phase field of the Fe-C phase diagram.

Within the austenite phase field, pre-existing carbides, carbonitrides, nitrides, and some inclusions dissolve into the matrix, with dissolution extent depending on welding parameters. Extensive dissolution permits austenite grain growth to large sizes. During rapid cooling, carbon and dissolved alloying elements remain trapped in solution during austenite transformation to bainite or martensite. Upon elevated temperature exposure during PWHT or service conditions, carbides such as M3C, M23C6, and M6C precipitate and nucleate on dislocations within grain interiors, causing precipitation strengthening and secondary hardening. These precipitates remain typically incoherent with the matrix, demonstrate stability at higher temperatures, retard dislocation movement, and restrict residual stress relaxation.

Impurity Segregation and Embrittlement Mechanisms

Investigations reveal that one primary SRC mechanism involves impurity segregation, especially phosphorus, to grain boundary/carbide interfaces or carbide-free grain boundary areas under high thermal tensile stresses developed during cooling. Research demonstrates that carbides possess higher interfacial energies than grain boundaries, making impurity segregation to carbide interfaces more probable than to grain boundaries, resulting in carbide interface embrittlement.

Phosphorus concentration reaches maximum levels at grain boundary/carbide interfaces, where intergranular cracking initiates. The matrix adjacent to grain boundaries may become depleted of alloying elements, creating denuded or precipitate-free zones that are softer and more ductile, causing strain localization in these regions.

Precise heat treatment following the addition of intergranular carbide-forming elements like titanium, vanadium, or niobium is recommended to inhibit carbide formation and growth at grain boundaries. Without proper PWHT, grain boundary/carbide interface strength decreases, and combined with segregation effects, leads to decohesion along these boundaries.

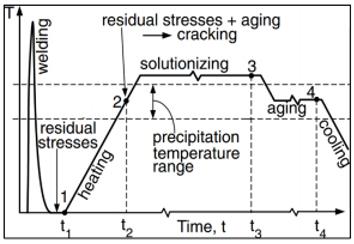

Figure 1: Schematic representation of typical thermal cycle for a weld HAZ

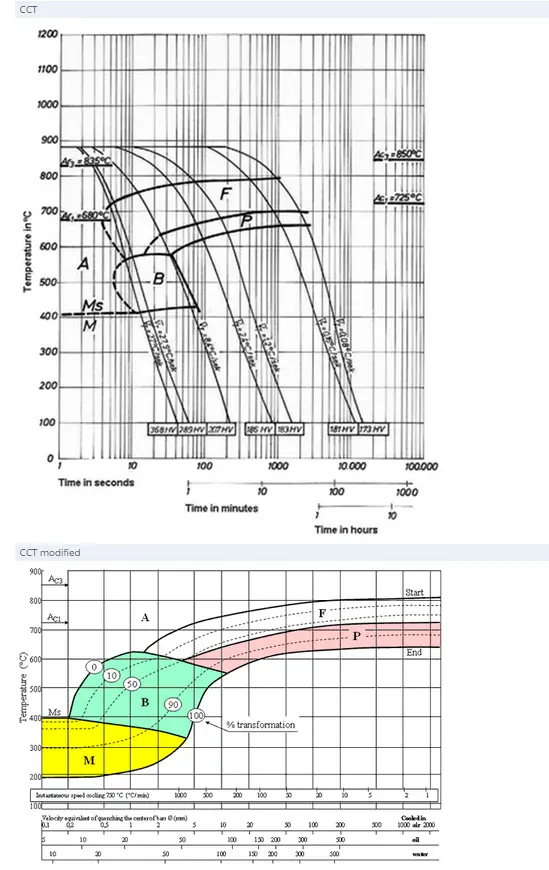

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.