Determining Hardening Depth Using Ultrasonic Backscatter

Abstract

In order to evaluate the wear characteristics it is advantageous to use a nondestructive method for measuring the thickness of the hardened surface layer, that is hardness depth.

Backscatter method was originally developed for determination of the hardness depth of large cast-steel rolls. However nowadays, due to the further development of instrument technology, it can be used on parts having small dimensions and, as shown here, can even be carried out with a portable ultrasonic flaw detector.

Many moving mechanical parts are surface hardened whilst their cores remain in the original structural condition. In order to evaluate the wear characteristics it is advantageous to use a nondestructive method for measuring the thickness of the hardened surface layer, that is hardness depth. Different solutions have therefore been published:

- using the magnetic and magnetic-electrical characteristics of this layer,

- using the sound velocity of ultrasonic waves, and

- using the backscatter of ultra-sonic waves.

With hardening of steels, by chilling after previous heating, the structure is converted from austenite to martensite. The surface layer has a fine structure and therefore does not scatter the ultrasonic waves so much as the non-converted core.

If transverse waves are used having a high frequency with a low bandwidth then a suitable ratio of grain size/wave length can be found so that the stepwise change in structure is visible on the display of the ultrasonic instrument by a stepwise change of the backscatter amplitude. In this case narrow band pulses are used with a center frequency of 20 MHz.

The transverse waves are beamed at an angle in order to measure, free from any interference, the time of flight between beam entry into the test object and the beginning of increased backscatter. The ultrasonic backscatter method directly reacts to changes in structure caused by the hardening of the surface layer.

The time of flight is measured between the sound entry and the beginning of the increased backscatter. Together with the known sound velocity Vtrans and the known angle of incidence , the thickness t of the hardened layer (hardness depth) is calculated according as:

Hardness depth

German DIN standard 50190 refers to the measurement of a hardness curve measured with indenters on test objects which have been cut, i.e. destructive testing. The hardness depth is, according to this standard, a point in the vertical direction which corresponds to a predetermined limit value (boundary hardness).Ultrasonic backscatter does react to changes in structure, however it can not be linked to a determined hardness value using the indentation method. If there is a sudden transition between the surface zone and the core then there is a strong in crease in backscatter. Due to the fact that there is a steep drop in the hardness curve at this boundary, this interface will approximately correspond to the position of the backscatter signal according to the hardness depth for such a case.

If there is a transitional structure, then the hardness curve and the backscatter curve will be flatter. The location of the boundary hardness and the location of the maximum backscatter do not coincide.

Measurement limitations using backscatter

The method cannot be used when no backscatter signals are received or if they cannot be separated from the interface echo; because the time measurement requires clear start and stop signals. Very thin layers below a thickness of 1.5 mm can therefore not be measured.All hardness processes which cause rapid structure conversion (with sound velocity) mostly produce a good detectable backscattering layer.

In all hardness processes which cause slow structure conversion, e.g. diffusion processes either produce a layer which is too thin, as nitriding does, or produce a wide zone with transition structure, as case hardening does, a steep increase of backscatter cannot be detected. The hardness depth, measured on the ground section according to DIN 50 190 Part 1, is 1.5 mm. Such a hardness depth could still be measured with the backscatter due to the narrow interface echo (entry). However, the steep increase of backscatter is missing in the transition from the surface layer to the core zone.

When the conversion process during hardening is incomplete, coarse grains remain in the hardened surface layer, so that strong backscatter of ultrasonic waves already take place there. Determination of the hardness depth via backscatter is, in these cases, at least erroneous if not impossible.

Calibration of the ultrasonic instrument

As already mentioned, the backscatter method is based on a time of flight measurement. This can be very accurately carried out by digital ultra sonic instruments. Readouts from digital displays also produce a very high degree of accuracy.A direct read off of the measured time of flight, even as a digital value, is possible when the display of the ultrasonic instrument is calibrated in time (in microseconds). The hardness depth t must be calculated with the displayed time of flight τ, the known sound velocity Vtrans and the known angle of incidence β according.

A second possibility offers the calibration of the display as half the sound path for transverse waves. The displayed half of the sound path s only needs to be multiplied by the factor cosβ.

With serial tests it is of advantage to let the instrument carry out this multiplication. This is achieved by using the calibration possibility for angle-beam probes.

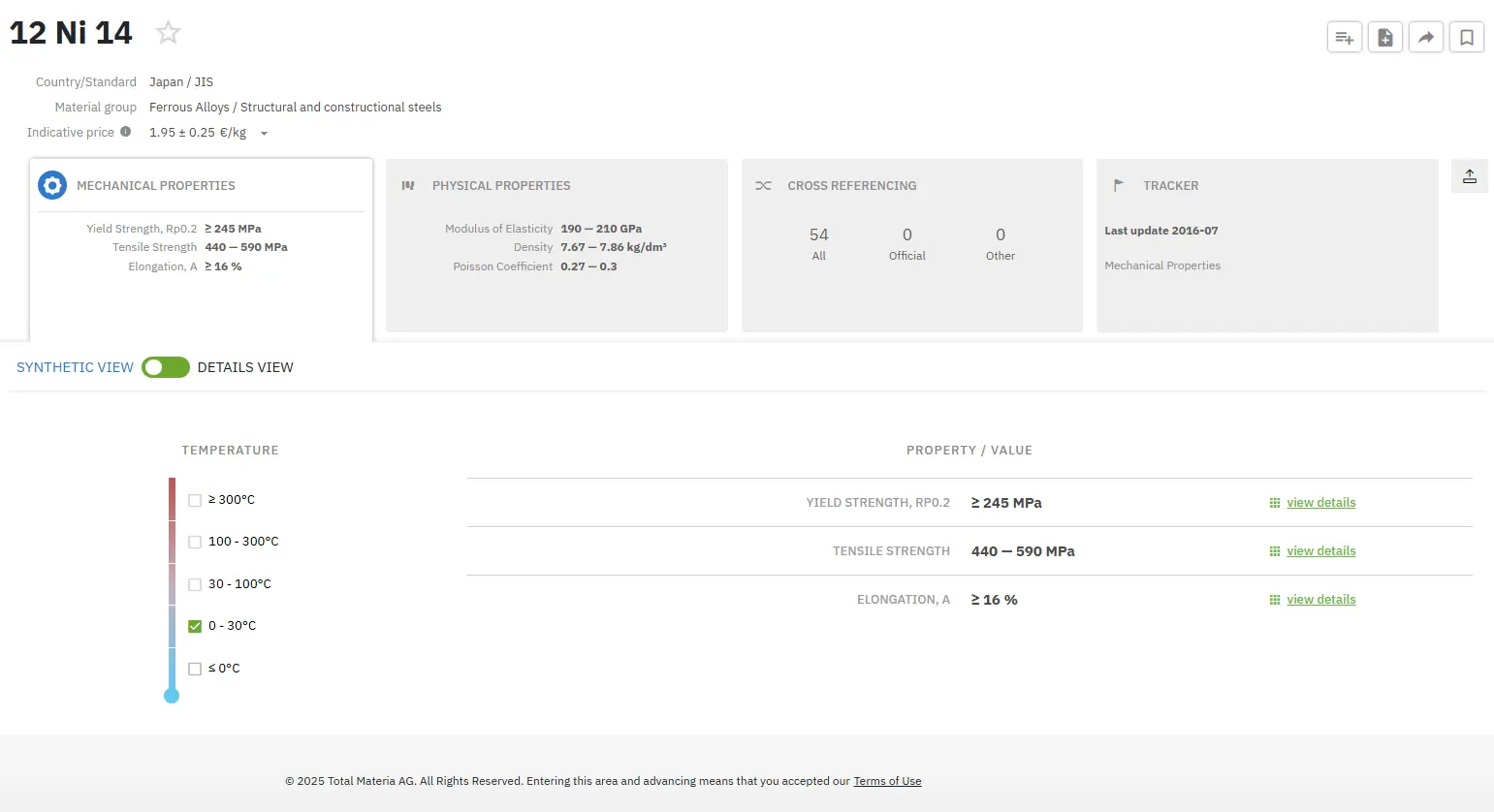

Find Instantly Precise Material Properties!

Total Materia Horizon contains mechanical and physical properties for hundreds of thousands of materials, for different temperatures, conditions and heat treatments, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.