Designing to Codes and Standards

Abstract

This article explores the fundamental importance of codes and standards in engineering design practice. Originating from the need for interchangeability and compatibility in manufacturing, these guidelines have evolved into essential tools for ensuring safety, quality, and consistency across industries. The text examines the distinctions between performance and specification codes, various types of standards from proprietary to international ones, and the processes through which they develop. It emphasizes the designer's professional responsibility to thoroughly research and adhere to applicable codes and standards, highlighting how they transform accumulated knowledge into practical design requirements while fulfilling government obligations to protect public welfare.

Introduction to Codes and Standards

The fundamental need for codes and standards in design is based on two concepts: interchangeability and compatibility. In the era of individual artisans, each manufactured item was unique, with parts custom-made to fit together. When replacement parts were needed, they had to be specially crafted to match the original.

However, as economies grew and mass production became necessary, this handcrafted approach proved inefficient. Economies of scale demanded that parts be nearly identical, with readily available replacements when needed. The critical factor was ensuring that replacement parts were interchangeable with the originals.

Most design projects involve creative problem-solving regardless of materials used. For highly advanced projects that push technical boundaries, designers must rely on basic science, intuition, and peer consultation to develop solutions. With skill, courage, resources, and patience, workable solutions typically emerge.

Nevertheless, most design projects aren't revolutionary but rather build upon established practices. Historically, such design knowledge was carefully guarded as trade secrets. Over time, these private methods became common knowledge and eventually evolved into published standards. Government entities, fulfilling their duty to protect public welfare and safety, incorporated many of these standards into legal frameworks.

The Need for Codes and Standards

The fundamental need for codes and standards in design is based on two concepts, interchangeability and compatibility. When manufactured articles were made by artisans working individually, each item was unique and the craftsman made the parts to fit each other. When a replacement part was required, it had to be made specially to fit.

However, as the economy grew and large numbers of an item were required, the handcrafted method was grossly inefficient. Economies of scale dictated that parts should be as nearly identical as possible, and that a usable replacement part would be available in case it was needed. The key consideration was that the replacement part had to be interchangeable with the original one.

Standardization of parts within a particular manufacturing company to ensure interchangeability is only one part of the industrial production puzzle. The other critical aspect is compatibility. The challenge arises when parts from one company, working to their standards, must be combined with parts from another company, working to different standards. Will parts from company A fit with parts from company B? They will only if the parts are compatible—meaning the standards of the two companies must align.

Purposes and Objectives of Engineering Codes and Standards

The protection of general welfare stands as a primary reason for establishing government regulatory frameworks. Codes assist these government agencies in fulfilling their obligation to protect the population they serve. The core objectives of codes are to prevent property damage and to minimize injury or loss of life by applying accumulated knowledge to avoid, reduce, or eliminate identifiable hazards.

It's essential to understand the distinction between "codes" and "standards." Codes tell users what to do and under what circumstances to do it. They often carry legal weight when adopted by local jurisdictions that enforce their provisions. Standards, on the other hand, explain how to accomplish tasks and typically function as recommendations without legal force.

As defined, codes frequently incorporate nationally recognized standards as reference material. It's common for local codes to reference these standards, sometimes adopting entire sections by reference, which then become legally enforceable requirements.

The relationship between codes and standards creates a comprehensive framework that guides designers through both mandatory requirements and recommended practices, ensuring both regulatory compliance and technical excellence in engineering design.

Evolution and Development of Industry Standards

Whenever a new field of economic activity emerges, inventors and entrepreneurs rush to enter the market using various approaches. Eventually, the initial chaos subsides, and a consensus forms regarding what constitutes "good practice" within that industry.

As industries mature and more companies become involved as suppliers, subcontractors, and assemblers, establishing national trade practices becomes the next critical step in standards development. Organizations like the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) provide the necessary forum for this process. Typically, a sponsoring trade association requests ANSI to review its standard. ANSI then forms a review group including members from diverse stakeholder groups beyond just the industry itself—an essential feature that expands the area of consensus.

ANSI circulates copies of proposed standards to all interested parties seeking comments within a specified timeframe. After the comment period, a Board of Standards Review considers all feedback and makes necessary changes. Following additional reviews, the standard is finally issued and published by ANSI, listed in their catalog, and made available for purchase.

The International Standards Organization (ISO) employs a similar process, having begun preparing an extensive set of worldwide standards in 1996. One key feature of the ANSI system is the unrestricted availability of its standards. Unlike company or proprietary standards that may be restricted, ANSI standards are accessible to everyone. This wide consensus format and easy accessibility mean designers have no excuse for not researching and collecting all standards applicable to their projects.

Classification of Code Types in Engineering Design

There are two broad categories of codes: performance codes and specification (or prescriptive) codes. Performance codes state requirements in terms of what must be achieved, focusing on results rather than methods. Specification codes provide specific details and leave little discretion to the designer. Both types are widely used in engineering practice.

Trade codes address various public welfare concerns. Plumbing, ventilation, and sanitation codes focus on health considerations. Electrical codes aim to prevent property damage and personal injury. Building codes establish structural requirements ensuring adequate load resistance. Mechanical codes address both component strength and injury prevention. These codes provide detailed guidance to designers of buildings and equipment that will be constructed, installed, operated, or maintained by skilled tradespeople.

Safety codes specifically address safety aspects of particular entities. They set forth detailed requirements for safe design and operation across numerous applications.

Professional societies have developed widely accepted codes. The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) publishes the Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code, a design standard used for decades. The Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) publishes recommended practices in various electrical disciplines. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) publishes hundreds of standards relating to vehicle design and safety requirements. The American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) publishes thousands of standards for materials and testing methods.

Statutory codes, prepared and adopted by governmental agencies at local, state, or federal levels, have the force of law and include enforcement provisions, licensing requirements, and penalties for violations. Thousands of these codes exist, each applicable within its geographical jurisdiction.

Regulations implement legislation by providing specific details. While laws passed by legislatures often use general language, agency staff write regulations that clarify implementation requirements and operational details.

Types of Standards in Engineering Practice

Proprietary Standards

Proprietary (in-house) standards are developed by individual companies for their own use. These standards typically establish tolerances for various physical factors such as dimensions, fits, forms, and finishes for internal production. When outsourcing, purchasing departments often incorporate these in-house standards into their order terms and conditions. Quality assurance provisions frequently follow in-house standards, though many now align with ISO 9000 requirements. Operating procedures for material review boards commonly build on in-house standards. Designers are expected to maintain thorough familiarity with their employer's standards as a fundamental job requirement.

Government Specification Standards

Government specification standards at federal, state, and local levels encompass thousands of documents. Because government purchases represent a substantial portion of the national economy, designers must become familiar with standards applicable to this massive market segment. To ensure purchasing agencies receive precisely the products they require, specifications are drawn up in extensive detail. Non-compliance with specifications typically results in rejection of seller offers, and these standards often include stringent inspection, certification, and documentation requirements.

Designers should note that government specifications, particularly Federal specifications, typically contain sections referencing other documents incorporated into the primary document. These referenced materials usually include federal specifications, federal and military standards, and applicable industrial or commercial standards. MIL standards and Handbooks for specific product lines should be essential resources for designers working in government supply.

Product and Commercial Standards

Product definition standards, published by the National Institute of Standards and Technology under Department of Commerce procedures, establish grading rules, specific variety names, and uniform dimensions for commonly used materials.

Commercial standards (designated by the letters CS) are published by the Commerce Department for commodity-type articles. Since vendors often commingle products from multiple suppliers, quality variations can occur. Commercial Standards provide a uniform basis for fair competition by establishing test methods, ratings, certification procedures, and labeling requirements.

International Standards

International standards have proliferated rapidly over the past two decades in response to global economy demands for uniformity, compatibility, and interchangeability. Beginning in 1987, the International Standards Organization (ISO) addressed quality assurance standardization, resulting in the ISO 9000 Standard for Quality Management. This was followed by ISO 14000 for Environmental Management Standards, addressing international environmental challenges.

ISO Technical Committees (TC) publish handbooks and standards in specialized fields, including ISO Standards Handbooks on Mechanical Vibration and Shock, Statistical Methods for Quality Control, and Acoustics. These resources provide valuable information for designers targeting international markets.

Standards Organizations and Resource Access

U.S. Government Documentation Resources

For Federal government procurement items outside the Department of Defense, the Office of Federal Supply Services within the General Services Administration publishes the Index of Federal Specifications, Standards and Commercial Item Descriptions annually each April. This comprehensive resource catalogs the extensive array of standards applicable to government contracting work.

ANSI and International Standards Access

The American National Standards Institute publishes a catalog of all their publications and distributes catalogs of standards published by 38 other ISO member organizations. ANSI also distributes ASTM and ISO standards along with English language editions of Japanese Standards, Handbooks, and Materials Data Books. However, ANSI does not handle publications from the British Standards Institute or the standards organizations in Germany and France.

As previously mentioned, many organizations sponsor standards that ANSI prepares using their consensus format. These sponsors provide valuable information on forthcoming changes in standards and should be consulted by designers wishing to avoid last-minute surprises. Listings in the ANSI catalog include the acronym for the sponsor after the ANSI symbol, with the field of interest typically evident from the organization's name.

Understanding these documentation resources and how to access them efficiently is a critical skill for engineering professionals working across diverse industries and regulatory environments.

Designer's Professional Responsibility Regarding Codes and Standards

Once a designer has established a clear definition of the problem and formulated a promising solution, the next logical step is to begin collecting available reference materials, including relevant codes and standards. This collection phase represents a key component of the design effort's background research. Awareness of applicable codes and standards' existence and relevance is a fundamental professional responsibility for every designer.

During the background phase, designers must ensure their collection of reference codes and standards is both complete and comprehensive. Given the vast amount of information available and its relative accessibility, this can be a formidable task. However, failing to acquire a complete collection of applicable standards is professionally risky in today's litigious environment.

More critically, a designer's failure to meet the requirements specified in these standards can constitute professional malpractice. The legal and ethical implications of neglecting applicable codes extend beyond simple technical oversight—they represent a breach of the designer's duty to protect public safety and welfare.

Engineering professionals must establish systematic approaches to identifying, obtaining, and implementing relevant codes and standards throughout their design processes. This responsibility forms a cornerstone of ethical engineering practice and helps ensure that designed products and systems meet established safety, compatibility, and performance requirements.

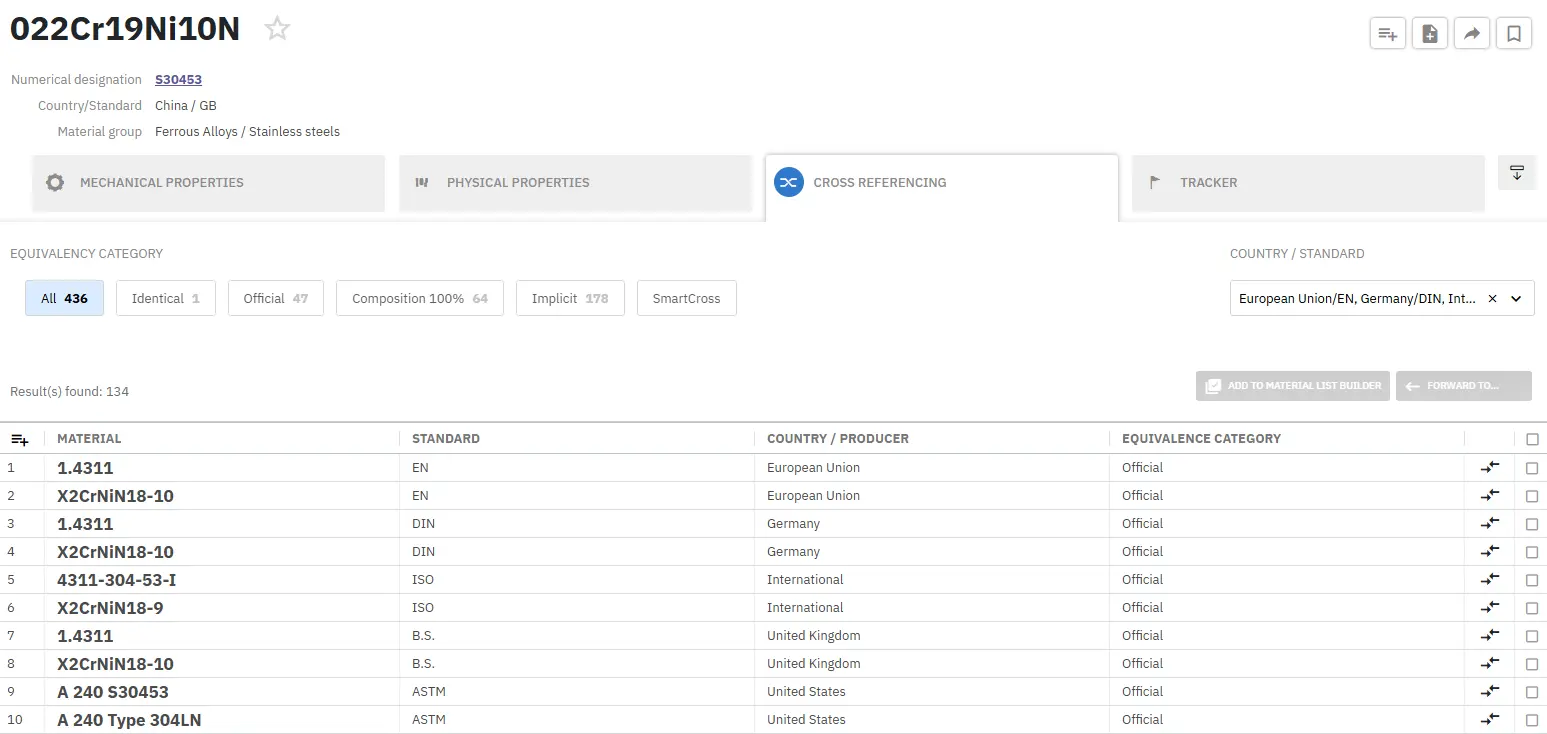

Instantly Find and Compare Materials from Different Standards!

Total Materia Horizon contains detailed and precise property information for hundreds of thousands of materials according to all standards worldwide, updated monthly.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.