Controlled rolling of low alloy steels

Abstract

The hot-rolling process has gradually become a much more closely controlled operation, and is being increasingly applied to low alloy steels with compositions carefully chosen to provide optimum mechanical properties when the hot deformation is complete. This process, in which the various stages of rolling are temperature-controlled, the amount of reduction in each pass is predetermined and the finishing temperature is precisely defined, is called controlled rolling and is now of greatest importance in obtaining reliable mechanical properties in steels for pipelines, bridges, and many other engineering applications.

The hot-rolling process has gradually become a much more closely controlled operation, and is being increasingly applied to low alloy steels with compositions carefully chosen to provide optimum mechanical properties when the hot deformation is complete. This process, in which the various stages of rolling are temperature-controlled, the amount of reduction in each pass is predetermined and the finishing temperature is precisely defined, is called controlled rolling and is now of greatest importance in obtaining reliable mechanical properties in steels for pipelines, bridges, and many other engineering applications.

On the other hand, in more highly alloy steels, it is possible to subject the steels to heavy deformations in the metastable austenitic conditions prior to transformation to martensite. This process, ausforming, allows the attainment of very high strength levels combined with good toughness and ductility.

Before World War II, strength in hot-rolled low alloy steels was achieved by the addition of carbon up to 0.4% and manganese up to 1.5%, giving yield stresses of 350-400 MPa. However, such steels are essentially ferrite pearlite aggregates, which do not possess adequate toughness for many modern applications. Indeed, the toughness, as measured by the ductile/brittle transition decreases dramatically with carbon content, i.e. with increasing volume of pearlite in the steel. Furthermore, with the introduction of welding as the main fabrication technique, the high carbon contents led to serious cracking problems, which could only be eliminated by the use of lower carbon steels. The great advantage of producing in these steels a fine ferrite grain size soon became apparent, so controlled rolling in the austenitic condition was gradually introduced to achieve this.

Fine ferrite grain sizes in the finished steel were found to be greatly expedited by the addition of small concentrations (< 0.1 wt %) of grain refining elements such as niobium, titanium, vanadium and aluminum. On adding such elements to steels with 0.03-0.08% C and up to 1.5% Mn, it became possible to produce fine-grained material with yield strengths between 450 and 550 MPa, and with ductile/brittle transition temperatures as low as -70°C. Such steels are now referred to as high strength low alloy steels (HSLA), or micro-alloyed steels. This progress, from the relatively low strength of ordinary mild steel (220-250 MPa) in a period of twenty years represents a major metallurgical development, the importance of which, in engineering applications, cannot be overstated.

The primary grain refinement mechanism in controlled rolling is the recrystallization of austenitic during hot deformation, known as dynamic recrystallization. This process is clearly influenced by the temperature and the degree of deformation, which takes place during each pass through the rolls. However, in austenite devoid of second phase particles, the high temperatures involved in hot rolling lead to marked grain growth, with the result that grain refinement during subsequent working is limited.

Clearly, the control of grain size at high austenitizing temperatures requires as fine a grain boundary precipitate as possible, and one which will not dissolve completely in the austenite, even at the highest working temperatures (1200-1300°C). The best grain refining elements are very strong carbide and nitride formers, such as niobium, titanium and vanadium, also aluminum which forms only a nitride. As both carbon and nitrogen are present in control-rolled steels, and as the nitrides are even more stable than the carbides it is likely that the most effective grain refining compounds are the respective carbo-nitrides, except in the case of aluminum nitride. As a result of the combined use of controlled rolling and fine dispersions of carbo-nitrides in low alloy steels, it has been possible to obtain ferrite grain sizes between 5 and 10 μm in commercial practice.

The solubility data implies that, in micro-alloyed steel, carbides and carbo-nitrides of Nb, Ti and V will precipitate progressively during controlled rolling as the temperature falls. While the primary effect of these fine dispersions is to control grain size, dispersion strengthening will take place. The strengthening arising from this cause will depend both on the particle size and the interparticle spacing which is determined by the volume fraction of precipitate. These parameters will depend primarily on the type of compound which is precipitating, and that is determined by the micro alloying content of the steel. However, the maximum solution temperature reached and the detailed schedule of the controlled rolling operation are also important variables.

It is now known, not only that precipitation takes place in the austenite, but that further precipitation occurs during the transformation to ferrite. The precipitation of niobium, titanium and vanadium carbides has been shown to take place progressively as the interphase boundaries move through the steel As this precipitation is normally on an extremely line scale occurring between 850 and 650°C, it is likely to be the major contribution to the dispersion strengthening. In view of the higher solubility of vanadium carbide in austenite, the effect will be most pronounced in the presence of this element, with titanium and niobium in decreasing order of effectiveness. If the rate of cooling through the transformation is high, leading to the formation of supersaturated acicular ferrite, the carbides will tend to precipitate within the grains, usually on the dislocations, which are numerous in this type of ferrite.

In arriving at optimum compositions of micro-alloyed steels, it should be noted that the maximum volume fraction of precipitate, which can be put into solid solution in austenite at high temperatures, is achieved by use of stoichiometric compositions.

In modern control-rolled micro-alloyed steels, there are at least three strengthening mechanisms, which contribute to the final strength achieved. The relative contribution from each is determined by the composition of the steel and, equally important, the details of the thermomechanical treatment to which the steel is subjected. Firstly, there are the solid solution strengthening increments from manganese, silicon and uncombined nitrogen. Secondly, the grain size contribution to the yield stress is shown as a very substantial component, the magnitude of which is very sensitive to the detailed thermomechanical history. Finally, a typical increment is dispersion strengthening. The total result is a range of yield strengths between about 350 and 500 MPa. In this particular example, the steel was normalized (air cooled) from 900°C, but had it been control rolled down to 800°C or even lower, the strength levels would have been substantially raised.

The effect of the finishing temperature for rolling is important in determining the grain size and, therefore, strength level reached for particular steel. It is now becoming common to roll through the transformation into the completely ferritic condition, and so obtain fine subgrain structures in the ferrite, which provide an additional contribution to strength. Alternatively, the rolling is finished above the γ/α transformation, and the nature of the transformation is altered by increasing the cooling rate. Slow rates of cooling obtained by coiling at a particular temperature will give lower strengths than rapid rates imposed by water spray cooling following rolling.

Dual phase steels are referred to as dual phase low alloy (DPLA) steels. They exhibit continuous yielding, i.e. no sharp yield point, and a relatively low yield stress (300-350 MPa) together with a rapid rate of work hardening and high elongations (≈ 30 %) which gives excellent formability. As a result of the work hardening, the yield stress in the final formed product is as high as in HSLA steels (500-700 MPa). The simplest steels in this category contain 0.08-0.2 % C, 0.5-1.5 % Mn, but steels micro-alloyed with vanadium are also suitable, while small additions of Cr (0.5 %) and Mo (0.2-0.4%) are frequently used.

The simplest way of achieving a duplex structure is to use intercritical annealing in which the steel is heated to the (α + γ) region between Ac1 and Ac3 and held, typically, at 790°C for several minutes to allow small regions of austenite to form in the ferrite. As it is essential to transform these regions to martensite, recooling must be rapid or the austenite must have a high hardenability. This can be achieved by adding between 0.2 and 0.4% molybdenum to the steel already containing 1.5 % manganese. The required structure can then be obtained by air-cooling after annealing.

To eliminate an extra heat treatment step, dual phase steels have now been developed. These steels can be given the required structure during cooling after controlled rolling. Typically, these steels have additions of 0.5% Cr and 0.4% Mo. After completion of hot rolling around 870°C, the steel forms approximately 80% ferrite on the water-cooled run-out table from the mill. The material is then cooled in the metastable region (510-620°C) below the pearlite/ferrite transformation and, on subsequent cooling, the austenite regions transform to martensite.

Micro-alloyed steels produced by controlled rolling are a most attractive proposition in many engineering applications because of their relatively low cost, moderate strength, and very good toughness and fatigue strength, together with their ability to be readily welded. They have, to a considerable degree, eliminated quenched and tempered steels in many applications.

These steels are most frequently available in control rolled sheet, which is then cooled over a range of temperatures between 750 and 550°C. The cooling temperature has an important influence as it represents the final transformation temperature, and this influences the microstructure. The lower this temperature, under the same conditions, the higher the strength achieved.

The normal range of yield strength obtained in these steels varies from about 350 to 550 MPa. The strength is controlled both by the detailed thermomechanical treatment, by varying the manganese content from 0.5 to 1.5 wt%, and by using the microalloying additions in the range 0.03 to above 0.1 wt%. Niobium is used alone, or with vanadium, while titanium can be used in combination with the other two carbide-forming elements. The interactions between these elements are complex, but in general terms niobium precipitates more readily in austenite than does vanadium as carbide or carbo-nitride, so it is relatively more effective as a grain refiner. The greater solubility of vanadium carbide in austenite underlines the superior dispersion strengthening potential of this element shared to a lesser degree with titanium. Titanium also interacts with sulphur and can have a beneficial effect on the shape of sulphide inclusions. Bearing in mind that the total effect of these elements used in conjunction is not a simple sum of their individual influence, the detailed metallurgy of these steels becomes extremely complex.

One of the most extensive applications is in pipelines for the conveyance of natural gas and oil, where the improved weldability due to the overall lower alloying content (lower hardenability) and, particularly, the lower carbon levels is a great advantage.

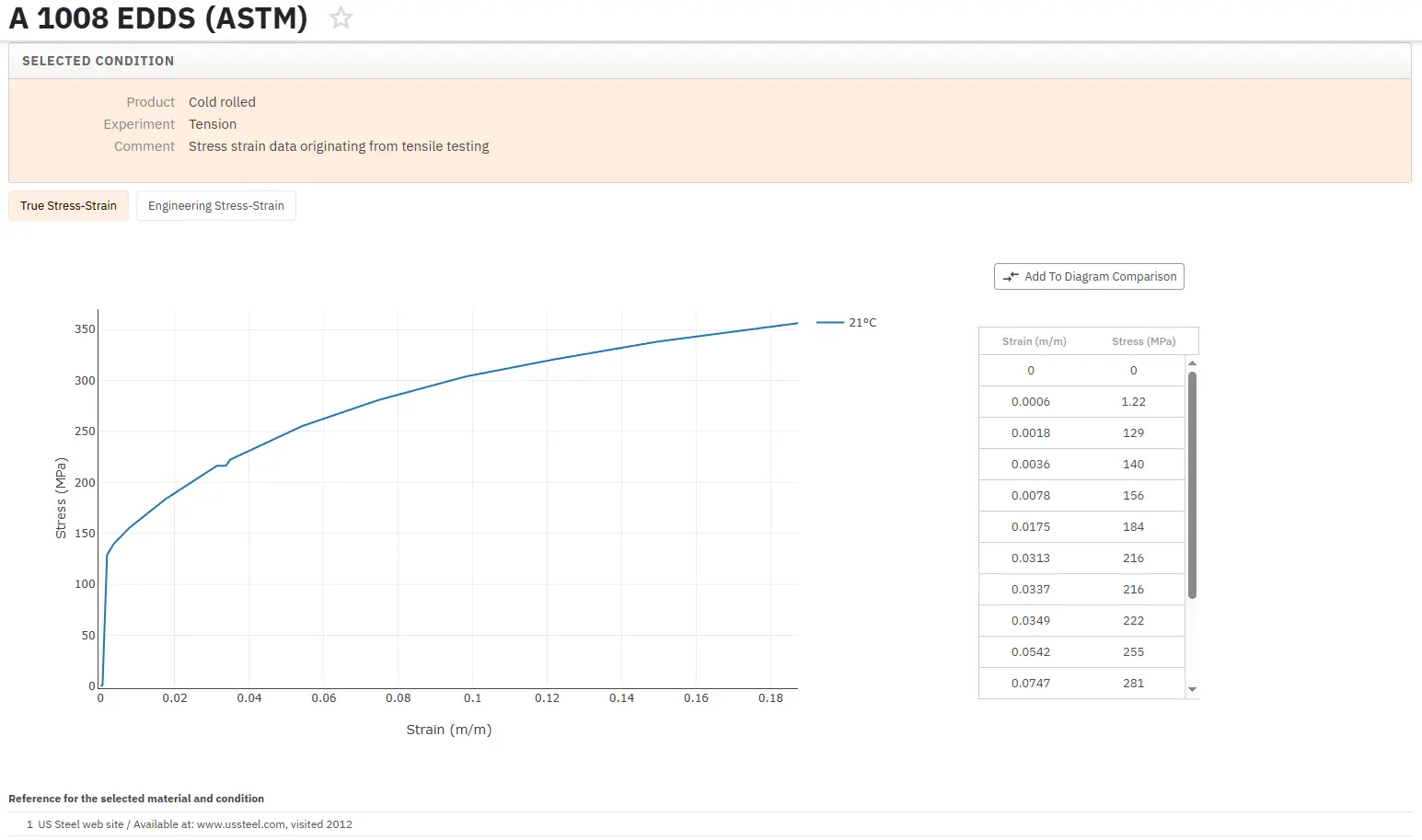

Access Precise Properties of Structural Steels Now!

Total Materia Horizon contains property information for 150,000+ structural steels: composition, mechanical and physical properties, nonlinear properties and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.