Heat Treating of Nodular Irons: Part One

Abstract

Nodular cast irons (or ductile, or spheroidal graphite iron) are primarily heat treated to create matrix microstructures and associated mechanical properties not readily obtained in the as-cast condition. As-cast matrix microstructures usually consist of ferrite or pearlite or combinations of both, depending on cast section size and/or alloy composition.

Nodular cast irons (or ductile, or spheroidal graphite iron) are primarily heat treated to create matrix microstructures and associated mechanical properties not readily obtained in the as-cast condition. As-cast matrix microstructures usually consist of ferrite or pearlite or combinations of both, depending on cast section size and/or alloy composition.

The most important heat treatments and their purposes are:

- Stress relieving, a low-temperature treatment, to reduce or relieve internal stresses remaining after casting

- Annealing, to improve ductility and toughness, to reduce hardness, and to remove carbides

- Normalizing, to improve strength with some ductility

- Hardening and tempering, to increase hardness or to improve strength and raise proof stress ratio

- Austempering, to yield a microstructure of high strength, with some ductility and good wear resistance

- Surface hardening, by induction, flame, or laser, to produce a locally selected wear-resistant hard surface

The normalizing, hardening, and austempering heat treatment, which involve austenitization, followed by controlled cooling or isothermal reaction, or a combination of the two, can produce a variety of microstructures and greatly extend the limits on the mechanical properties of ductile cast iron.

These microstructures can be separated into two broad classes:

- Those in which the major iron-bearing matrix phase is the thermodynamically stable body-centered cubic (ferrite) structure

- Those with a matrix phase that is a meta-stable face-centered cubic (austenite) structure.

The former are usually generated by the annealing, normalizing, normalizing and tempering, or quenching and tempering processes. The latter are generated by austempering, an isothermal reaction process resulting in a product called austempered ductile iron (ADI).

Other heat treatments in common industrial use include stress-relief annealing and selective surface heat treatment. Stress-relief annealing does not involve major micro-structural transformations, whereas selective surface treatment (such as flame and induction surface hardening) does involve microstructural transformations, but only in selectively controlled parts of the casting.

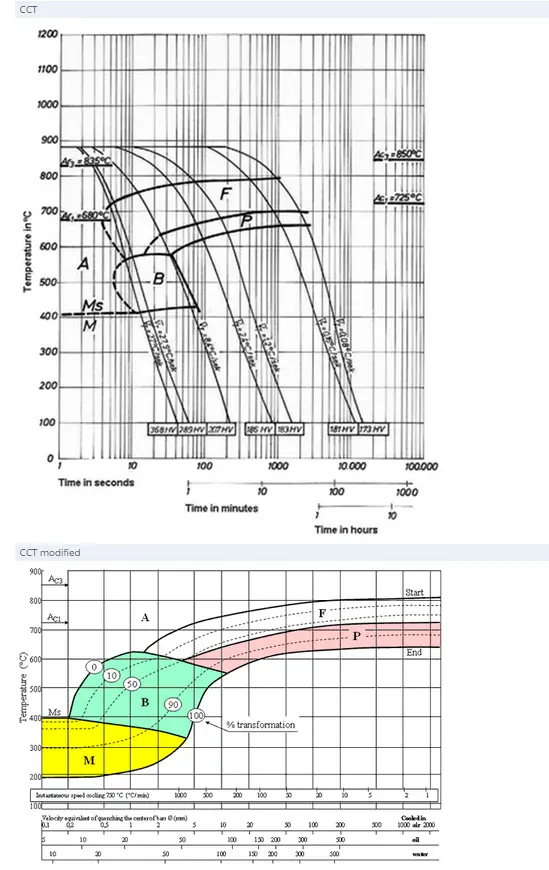

The basic structural differences between the ferritic and austenitic classes are explained in the Fig 1 and 2. Figure 1 shows a continuous cooling transformation (CCT) diagram and cooling curves for furnace cooling, air-cooling, and quenching.

It can be seen from Fig 1 that slow furnace cooling results in a ferritic matrix (the desired product of annealing), whereas the cooling curve for air cooling, or normalizing, results in a pearlitic matrix, and quenching produces a matrix microstructure consisting mostly of martensite with some retained austenite. Tempering softens the normalized and quenched conditions, resulting in microstructures consisting of the matrix ferrite with small panicles of iron carbide (or secondary graphite).

Figure 1: CCT diagram showing annealing, normalizing and quenching;

Ms stand martensite start, Mf for martensite finish.

Figure 2 shows an isothermal transformation (IT) diagram for a ductile cast iron, together with a processing sequence depicting the production of ADI. In this process, austenitizing is followed by rapid quenching (usually in molten salt) to an intermediate temperature range for a time that allows the unique metastable carbon-rich (≈2% C) austenitic matrix (γH) to evolve simultaneously with nucleation and growth of a plate-like ferrite (α) or of ferrite plus carbide, depending on the austempering temperature and time at temperature.

This austempering reaction progresses to a point at which the entire matrix has been transformed to the metastable product (stage I in Fig 2), and then that product is "frozen in" by cooling to room temperature before the true bainitic ferrite plus carbide phases can appear (stage II in Fig 2).

In ductile cast irons the presence of 2 to 3 wt% Si prevents the rapid formation of iron carbide (Fe3C). Hence the carbon rejected during ferrite formation in the first stage of the reaction (stage I in Fig 2) enters the matrix austenite, enriching it and stabilizing it thermally to prevent martensite formation upon subsequent cooling. Thus the processing sequence in Fig 2 shows that the austempering reaction is terminated before stage II begins and illustrates the decrease in the martensite start (Ms) and martensite finish (Mf) temperatures as γH forms in stage I. Typical austempering times range from 1 to 4 h depending on alloy content and section size. If the part is austempered too long, undesirable bainite will form. Unlike steel, bainite in cast iron microstructures exhibits lower toughness and ductility.

Figure 2: IT diagram of a processing sequence for austempering.

Read more

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.