Hardness Testing

Abstract

Hardness testing is a fundamental method for evaluating material properties, particularly resistance to permanent deformation. This article explores the primary hardness measurement techniques, including scratch, indentation, and dynamic methods, with special emphasis on indentation tests like Brinell, Meyer, Vickers, Rockwell, and microhardness tests. Each method's principles, applications, and limitations are discussed, along with mathematical formulations for calculating hardness values. The relationship between hardness and temperature is also examined, demonstrating how elevated temperatures affect material hardness through established mathematical models that correlate with changes in deformation mechanisms.

Introduction to Material Hardness

The hardness of a material represents a complex property with varying definitions depending on one's professional perspective. Generally, hardness indicates a material's resistance to deformation, and specifically for metals, it measures their resistance to permanent or plastic deformation. To materials testing specialists, hardness typically refers to indentation resistance, while design engineers often view it as a measurable quantity that provides insights into a metal's strength and heat treatment characteristics.

Hardness measurements fall into three general categories based on testing methodology:

- Scratch hardness

- Indentation hardness

- Rebound (dynamic) hardness

Among these, indentation hardness holds the greatest significance for engineering applications with metals.

Scratch and Dynamic Hardness Methods

Scratch hardness primarily serves mineralogists who classify materials based on their ability to scratch one another. The Mohs' scale, consisting of 10 standard minerals arranged by scratch resistance, provides the measurement standard. This scale ranges from talc (hardness 1) to diamond (hardness 10). However, the Mohs' scale has limited application for metals since most hard metals fall within the relatively narrow range of 4 to 8, and the intervals lack sufficient spacing in the high-hardness range.

Dynamic hardness testing typically involves dropping an indenter onto the metal surface, with hardness expressed as impact energy. The Shore scleroscope exemplifies this approach, measuring hardness according to the indenter's rebound height.

Brinell Hardness Test

The Brinell test, introduced by J.A. Brinell in 1900, became the first widely accepted standardized indentation hardness test. This method involves indenting the metal surface with a 10-mm-diameter steel ball under a load of 3,000 kg mass (approximately 29,400 N). For softer metals, the load is reduced to 500 kg to prevent excessive indentation, while tungsten carbide balls replace steel when testing very hard metals to minimize indenter distortion.

The standard procedure applies the load for 30 seconds, after which the indentation diameter is measured using a low-power microscope. The final measurement should average two diameter readings taken at right angles.

The Brinell hardness number (BHN) equals the load P divided by the indentation's surface area, calculated using the formula:

Where:

- P = applied load in N

- D = ball diameter in mm

- d = indentation diameter in mm

- t = impression depth in mm

The BHN units are MPa. Importantly, unless P/D² remains constant, the BHN typically varies with load, generally reaching maximum value at some intermediate load. Consequently, covering the entire range of commercial metal hardnesses with a single load is impractical.

The Brinell test's relatively large impression provides an advantage in averaging out local heterogeneities and reduces sensitivity to surface scratches and roughness compared to other hardness tests. However, this large impression size may preclude testing small objects or critical stress-bearing components where the indentation could potentially initiate failure.

Meyer Hardness Test

Meyer proposed a more rational hardness definition based on the indentation's projected area rather than its surface area. Meyer hardness equals the load divided by the projected indentation area, representing the mean pressure between the indenter surface and the indentation.

Like Brinell hardness, Meyer hardness is measured in MPa but demonstrates less sensitivity to applied load. In cold-worked materials, Meyer hardness remains essentially constant regardless of load, whereas Brinell hardness decreases as load increases. In annealed metals, Meyer hardness continuously increases with load due to strain hardening from the indentation, while Brinell hardness first increases then decreases at higher loads.

Despite being a more fundamental measure of indentation hardness, Meyer hardness seldom sees practical application in routine measurements.

Meyer proposed an empirical relationship between load and indentation size, commonly called Meyer's law:

P = kdn’

Where:

- n' = slope of the straight line when plotting log P against log d

- k = value of P when d = 1

Fully annealed metals typically have n' values around 2.5, while fully strain-hardened metals have n' values approximately 2. This parameter roughly corresponds to the strain-hardening coefficient in the exponential equation for the true stress-true strain curve, with the exponent in Meyer's law approximately equaling the strain-hardening coefficient plus 2.

Vickers Hardness Test

The Vickers hardness test employs a square-base diamond pyramid indenter with an included angle of 136° between opposite faces. This angle was selected to approximate the optimal ratio of indentation diameter to ball diameter in Brinell testing.

Due to the indenter shape, this is frequently called the diamond-pyramid hardness test. The diamond-pyramid hardness number (DPH), or Vickers hardness number (VHN or VPH), equals the load divided by the indentation's surface area. This area is calculated from microscopic measurements of the impression's diagonal lengths using the equation:

Where:

- P = applied load in kg

- L = average diagonal length in mm

- θ = angle between opposite diamond faces = 136°

The Vickers test has gained considerable acceptance in research applications because it provides a continuous hardness scale for a given load, ranging from very soft metals (DPH 5) to extremely hard materials (DPH 1,500). ASTM Standard E92-72 describes the Vickers hardness test procedure.

Rockwell Hardness Test

The Rockwell hardness test represents the most widely used hardness testing method. Its popularity stems from its speed, freedom from operator error, ability to distinguish slight hardness differences in hardened steel, and small indentation size that allows testing finished heat-treated parts without damage.

This test measures hardness based on indentation depth under constant load. The procedure begins with applying a 10 kg minor load to seat the specimen, minimizing required surface preparation and reducing indenter ridging or sinking. After applying the major load, the indentation depth is automatically recorded on a dial gauge using arbitrary hardness numbers.

The dial features 100 divisions, each representing 0.00008 inch (0.002 mm) penetration. The dial operates in reverse, so small penetration (higher hardness) produces higher hardness numbers, consistent with other hardness scales. Unlike Brinell and Vickers hardness measurements with MPa units, Rockwell hardness numbers are purely arbitrary.

Major loads of 60, 100, and 150 kg are commonly used. Since Rockwell hardness depends on both load and indenter, specifying the combination is necessary by prefixing the hardness number with a letter indicating the scale. A Rockwell hardness number without this letter prefix is meaningless.

Hardened steel testing typically uses the C scale with a diamond indenter and 150 kg major load, with useful readings ranging from RC 20 to RC 70. Softer materials generally use the B scale with a 1/16-inch-diameter steel ball and 100 kg major load, covering the range from RB 0 to RB 100. The A scale (diamond penetrator, 60 kg major load) provides the most extended scale for materials ranging from annealed brass to cemented carbides. Additional scales exist for specialized applications.

For reliable Rockwell hardness testing, several precautions should be observed:

- The indenter and anvil must be clean and properly seated

- Test surfaces should be clean, dry, smooth, and oxide-free (rough-ground surfaces typically suffice)

- The surface should be flat and perpendicular to the indenter

- Tests on cylindrical surfaces yield low readings, with error depending on curvature, load, indenter, and material hardness

- Specimen thickness should exceed the indentation depth by at least 10 times

- Spacing between indentations should be three to five times the indentation diameter

- Load application speed should be standardized using the Rockwell tester dashpot

Microhardness Testing Methods

Many metallurgical applications require hardness determination over extremely small areas, such as measuring hardness gradients at carburized surfaces, determining individual microstructure constituent hardness, or checking delicate component hardness. While scratch hardness tests can address these needs, indentation hardness tests have proven more useful.

The development of the Knoop indenter by the National Bureau of Standards and the Tukon tester's introduction for controlled application of loads as low as 25 g have made microhardness testing a standard laboratory procedure.

The Knoop indenter is a diamond ground to a pyramidal form producing a diamond-shaped indentation with long and short diagonals in an approximate 7:1 ratio, creating plane strain in the deformed region. The Knoop hardness number (KHN) equals the applied load divided by the unrecovered projected indentation area.

The Knoop indenter's special shape enables placing indentations much closer together than with square Vickers indentations, facilitating steep hardness gradient measurement. Additionally, for a given long diagonal length, the Knoop indentation's depth and area are only about 15 percent of a comparable Vickers indentation. This proves particularly useful when measuring thin layer hardness (such as electroplated coatings) or testing brittle materials where fracture tendency correlates with stressed material volume.

Hardness at Elevated Temperatures

Interest in elevated temperature hardness measurement has increased with efforts to develop improved high-temperature strength alloys. Hot hardness testing provides valuable indicators of an alloy's potential usefulness in high-temperature applications.

In a comprehensive review of temperature-dependent hardness data, Westbrook demonstrated that hardness temperature dependence follows the expression:

H = Ae-BT

Where:

- H = hardness in kg/mm²

- T = test temperature in K

- A,B = constants

Plotting log H versus temperature for pure metals typically yields two straight lines with different slopes. The slope change occurs at approximately half the metal's melting point temperature. Similar behavior appears in plots of logarithmic tensile strength versus temperature. This slope change likely results from changing deformation mechanisms at higher temperatures.

Plotting log H versus temperature for pure metals typically yields two straight lines with different slopes. The slope change occurs at approximately half the metal's melting point temperature. Similar behavior appears in plots of logarithmic tensile strength versus temperature. This slope change likely results from changing deformation mechanisms at higher temperatures.

The constant B, derived from the curve slope, represents the hardness temperature coefficient. This constant relates in a complex manner to the rate of heat content change with increasing temperature. These correlations enable reasonably accurate calculation of pure metal hardness as a function of temperature up to approximately half its melting point.

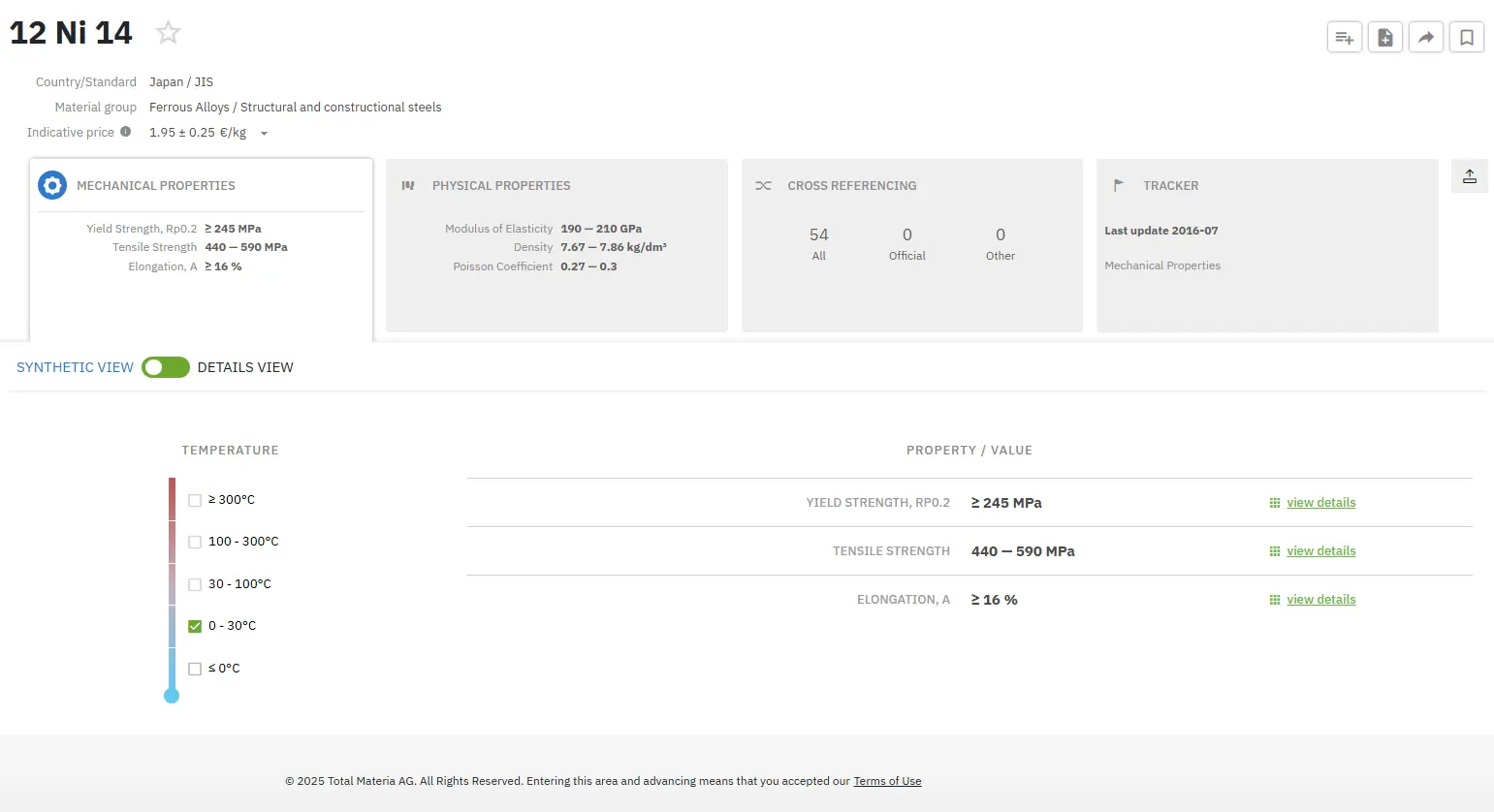

Find Instantly Precise Material Properties!

Total Materia Horizon contains mechanical and physical properties for hundreds of thousands of materials, for different temperatures, conditions and heat treatments, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.