Heat Treatment of High-Speed Steels

Abstract

This article examines the evolution and heat treatment characteristics of high-speed steels, from the pioneering T1 type to modern variants like M2 and M42. It details critical aspects of heat treatment processes, including hardening temperatures, tempering procedures, and their effects on mechanical properties. The comprehensive analysis covers microstructural changes, hardness variations, and specific applications, providing essential guidelines for achieving optimal tool performance through proper heat treatment parameters.

Historical Development and Basic Compositions

The T1 type high-speed steel, developed at the century's beginning and designated as 18-4-1, established the foundation for modern high-speed steels. This grade maintains limited use today, with enhanced versions incorporating 5-10% Co and increased carbon and vanadium contents for improved wear resistance. The characteristic hardening temperature range of 1260-1280°C remains safe for processing these steels.

Molybdenum has successfully replaced tungsten in many applications, leading to the development of M2 (6-5-4-2) and M7 grades. The M7 variant, containing higher molybdenum but lower tungsten than M2, offers superior toughness and wear resistance for specific applications. The M42 grade, a cobalt-enhanced version of M7, provides increased hot wear resistance. These M-series steels typically require hardening temperatures of 1200-1220°C, never exceeding 1230°C.

|

|

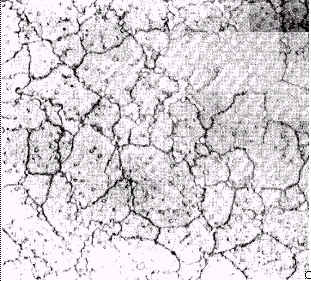

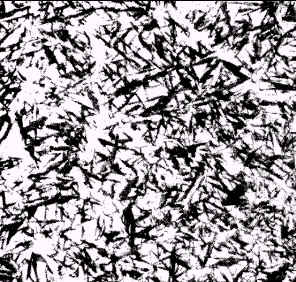

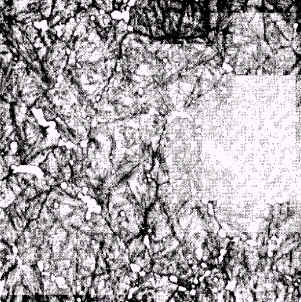

| (a) As quenched, 35% retained austenite; | (b) Tempered once at 600°C, 1 h. Tempered martensite and newly formed martensite; |

|

|

| (c) Tempered twice at 600°C. 1 h each time. Tempered martensite 700 x |

Figure 1. High-speed steel M42. Microstructure after oil hardening from 1200°C:

Heat Treatment Parameters and Considerations

The hardening process requires careful control due to the high temperatures involved. Chromium carbides dissolve around 1100°C, while approximately 10% of carbides, primarily vanadium and molybdenum-tungsten double carbides, remain undissolved at normal hardening temperatures.

|

|

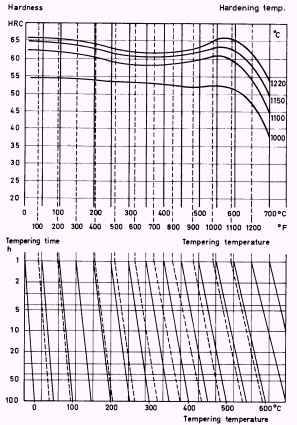

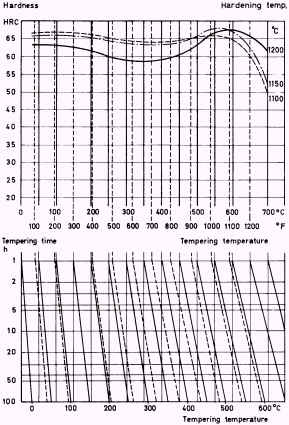

| Figure 2. Tempering curves showing inter-depedance of time and temperature for steel M2 | Figure 3. Tempering curves showing inter-depedance of time and temperature for steel M42 |

Tempering Characteristics and Properties

After quenching, these steels contain 20-40% retained austenite. Tempering at approximately 575°C transforms this austenite to martensite, requiring a second tempering treatment for optimal properties.

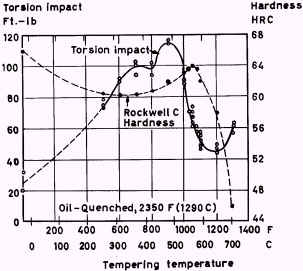

Figure 4. Influence of tempering temperature on hardness and torsion impact properties of grade T1 high-speed steel, oil hardened from 1290°C (2350°F)

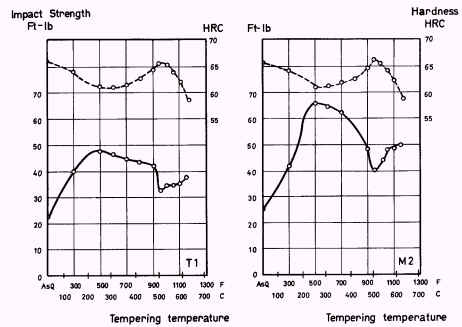

Figure 5. Influence of tempering temperature on hardness and unnotched Izod impact strength of grade T1 high-speed steel, austenitized at 1200°C (2350 °F), and grade M2, austenitized at 1220°C (2225 °F), respectively

Hot Hardness and Applications

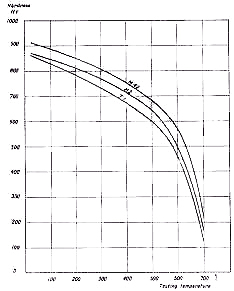

High-speed steels maintain significant hardness up to 500°C, crucial for cutting tools operating at elevated temperatures.

Figure 6. Hot-hardness of high-speed steels

These steels excel in machining applications, with highly alloyed grades like M42 performing best in high-speed cutting operations. They also serve in punching, blanking, and hot-work applications, with potential for enhanced wear resistance through carburizing or nitriding.

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

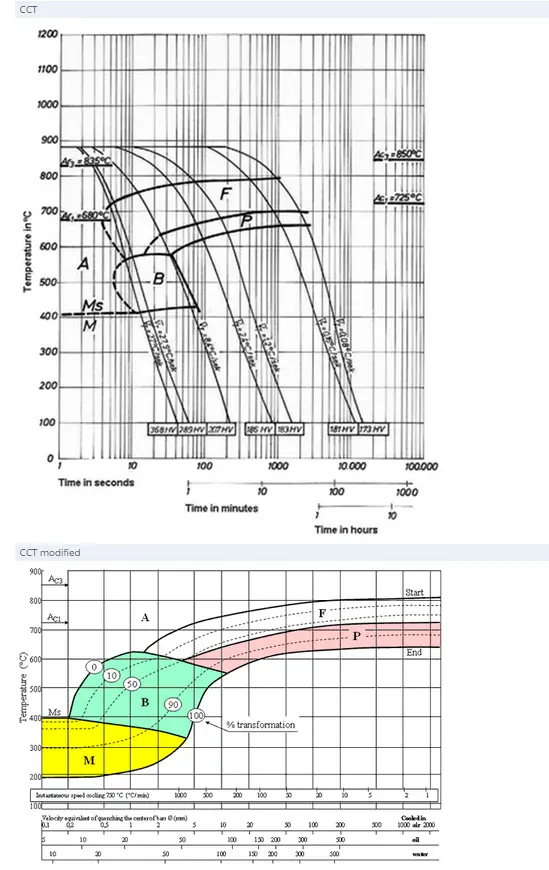

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.