Modification and Refinement of Aluminum-Silicon Alloys

Abstract

This article examines techniques for enhancing aluminum-silicon alloys through structural modification and refinement. For hypoeutectic alloys (5% Si to eutectic concentration), elements like sodium, strontium, calcium, and antimony enable finer eutectic structures, improving mechanical properties and castability. In hypereutectic compositions, phosphorus additions effectively refine primary silicon crystals, eliminating harmful coarse structures. The article details optimal modifier concentrations, application methods, and the critical impact of phosphorus content. Additionally, it addresses the importance of metal preparation processes—including hydrogen reduction and oxide removal—for ensuring casting quality across different manufacturing methods. These treatments significantly enhance mechanical properties, machinability, and overall casting performance in aluminum-silicon alloy components.

Introduction to Aluminum-Silicon Alloy Improvement

Hypoeutectic aluminum-silicon alloys can be significantly improved by inducing structural modification of the normally occurring eutectic. The greatest benefits are typically achieved in alloys containing from 5% silicon to the eutectic concentration, which encompasses most common gravity cast compositions used in industrial applications.

For hypereutectic compositions, the primary concern is the elimination of large, coarse primary silicon crystals that adversely affect both casting and machining operations. This objective is accomplished through primary silicon refinement processes that alter the microstructure.

The addition of specific elements—calcium, sodium, strontium, and antimony—to hypoeutectic aluminum-silicon alloys produces a finer lamellar or fibrous eutectic network. While increased solidification rates also contribute to similar structural improvements, chemical modification offers more consistent and controllable results.

Though experts debate the precise mechanisms involved, the most widely accepted explanations suggest that modifying additions suppress the growth of silicon crystals within the eutectic, resulting in a finer distribution of lamellae relative to the eutectic growth.

Comparative Effectiveness of Modifiers

Sodium, strontium, and calcium produce similar modification results, though with varying degrees of effectiveness. Research has established sodium as the superior modifier, followed by strontium and calcium, respectively. These elements are mutually compatible, allowing for combination additions without adverse interactions. However, it's important to note that eutectic modification achieved through these elements is transient rather than permanent.

Antimony offers a different approach as a permanent modifier, though the resulting structure differs significantly. Instead of the uniform, lace-like dispersed structures achieved with sodium, calcium, or strontium modification, antimony produces a more acicular refined eutectic. Consequently, the improvements in castability and mechanical properties are not as comprehensive as those achieved with the other modifying elements.

Structural refinement becomes time-independent when two critical conditions are met:

- The metal being treated must contain minimal phosphorus

- The velocity of the solidification front must exceed a minimum value approximately equal to that obtained in conventional permanent mold casting

A significant limitation of antimony is its incompatibility with other modifying elements. When antimony is present alongside other modifiers, coarse antimony-containing intermetallics form, preventing effective modification and negatively impacting casting outcomes.

Hydrogen Considerations with Modifiers

Modifier additions typically increase hydrogen content in the melt. With sodium and calcium, the solution reactions are often turbulent or accompanied by compound reactions that inherently increase dissolved hydrogen levels. For strontium, master alloys may contain significant hydrogen contamination, and evidence suggests that hydrogen solubility increases after alloying.

When using sodium, calcium, or strontium modifiers, hydrogen removal through reactive gases simultaneously removes the modifying element. The recommended practice involves adding modifying elements to well-processed melts, followed by inert gas fluxing to reduce hydrogen to acceptable levels. Antimony modification does not present these challenges.

Application Methods and Concentrations

Calcium and sodium can be added to molten aluminum in either metallic or salt form, with vacuum-prepackaged sodium metal being a common delivery method. Strontium is available in various forms, including aluminum-strontium master alloys (ranging from approximately 10% to 90% Sr) and Al-Si-Sr master alloys with varying strontium content.

Effective modification requires very specific concentrations:

- Sodium: Very low concentrations (approximately 0.001%) are sufficient, though typical additions achieve 0.005% to 0.015% sodium content, with remodification performed as needed

- Strontium: Effective in the range of 0.008% to 0.015%, though industry practice often uses 0.015% to 0.050%, with less frequent remodification compared to sodium

- Antimony: Must be alloyed to approximately 0.06% to be effective, though practical applications typically use 0.10% to 0.50%

The Critical Role of Phosphorus in Modification and Associated Benefits

Phosphorus significantly interferes with modification mechanisms. It reacts with sodium and likely with strontium and calcium to form phosphides that neutralize the intended modification additions. Therefore, using low-phosphorus metal is essential when modification is a process objective, and larger modifier additions may be necessary to compensate for phosphorus-related losses.

Primary producers can control phosphorus content during smelting and processing to maintain levels below 5 ppm in alloyed ingot. At these concentrations, normal modifier additions effectively achieve modified structures. However, phosphorus contamination can occur in foundry operations through exposure to phosphate-bonded refractories and mortars, or from phosphorus contained in melt additions like master alloys and silicon-containing alloying elements.

Modified structures typically exhibit somewhat higher tensile properties and significantly improved ductility compared to similar unmodified structures. Performance improvements in casting include enhanced flow and feeding capabilities and superior resistance to elevated-temperature cracking.

Refinement of Hypereutectic Aluminum-Silicon Alloys

The refinement of primary silicon crystals is essential for hypereutectic aluminum-silicon alloys to eliminate large, coarse structures that impair casting and machining operations. This refinement is achieved through phosphorus additions to melts containing silicon concentrations above the eutectic level.

Phosphorus can be added in various forms, including metallic phosphorus or phosphorus-containing compounds such as phosphor-copper and phosphorus pentachloride. Research demonstrates that trace concentrations as low as 0.0015% to 0.03% P effectively achieve refined structures. Historical disagreements about recommended phosphorus ranges and addition rates stem from the difficulty of accurately sampling and analyzing phosphorus content. Modern developments in vacuum stage spectrographic or quantometric analysis now provide more rapid and accurate phosphorus measurements.

Persistence of Refinement Effects

Unlike conventional modification in hypoeutectic alloys, refinement effects following phosphorus treatment tend to be less transient. Repeated testing involving solidification, cooling, reheating, remelting, and resampling shows that refinement persists, though primary silicon particle size gradually increases as phosphorus concentration decreases. Common degassing methods, especially those using chlorine or freon, accelerate phosphorus loss. Brief inert gas fluxing is often employed to reactivate aluminum phosphide nuclei, presumably through resuspension.

Recommended Refinement Practices

For effective melt refinement, the following practices are recommended:

- Maintain minimal melting and holding temperatures

- Thoroughly flux the alloy with chlorine or freon before refinement to remove phosphorus-scavenging impurities like calcium and sodium

- Perform brief fluxing after phosphorus addition to remove introduced hydrogen and distribute aluminum phosphide nuclei uniformly throughout the melt

Properly executed refinement substantially improves mechanical properties and castability. In some applications, particularly with higher silicon concentrations, refinement is essential for achieving acceptable foundry results.

Compatibility of Modification and Refinement

No elements are currently known to beneficially affect both eutectic and hypereutectic phases simultaneously. The potential negative interactions between modifying and refining additions in the melt manifest in the reaction of phosphorus with calcium, sodium, and strontium. While strontium has been claimed to benefit both hypoeutectic and hypereutectic structures, this claim lacks substantial verification.

Metal Preparation for Casting Applications

Regardless of the melting and holding furnace types or specific gravity casting process employed, reducing or eliminating dissolved hydrogen and entrained oxides remains a primary concern. These procedures are less frequently applied in pressure die casting, where focus shifts to addressing process-related causes of casting unsoundness, particularly entrapped gas and injection-associated inclusions.

Sensitivity to melt quality varies according to the casting process and part design, necessitating specialized consideration of relevant criteria for each application. Generally, melt processing aims to reduce hydrogen and remove oxides to meet specific casting requirements. Modification and grain-refiner additions are made as appropriate for the given alloy and end product.

Die Casting Considerations

Die casting operations employ different melt preparation practices because process-related conditions more strongly influence product quality than melt treatment factors. Consequently, degassing for hydrogen removal, grain refinement, and modification or silicon refinement (for hypereutectic silicon alloys) are sometimes intentionally omitted. However, the trend toward higher-integrity die castings has highlighted the importance of the same melt quality parameters established for gravity casting of aluminum alloys.

In high-volume die casting operations, efficiently processing internal and external scrap is crucial for reducing base metal costs, particularly for the predominantly secondary alloy compositions used. Scrap preparation typically involves crushing, shredding, and various pre-treatments before melting, often in efficient induction systems.

Oxides that become entrained in the melt during these operations are addressed using salts and/or reactive gas fluxing. A particular concern in die casting is the formation of complex intermetallics that remain insoluble at melt-holding temperatures or precipitate during holding, transfer, or injection. These intermetallics (sludge) affect furnaces, transfer systems, and casting quality through inclusion.

Die casters employ composition limits to prevent sludge formation. A common guideline suggests that the sum of iron content plus twice the manganese content plus three times the chromium content should not exceed 1.7%. This somewhat arbitrary limit, often assigned values between 1.5% and 1.9%, must be adjusted based on specific composition and actual minimum process temperature.

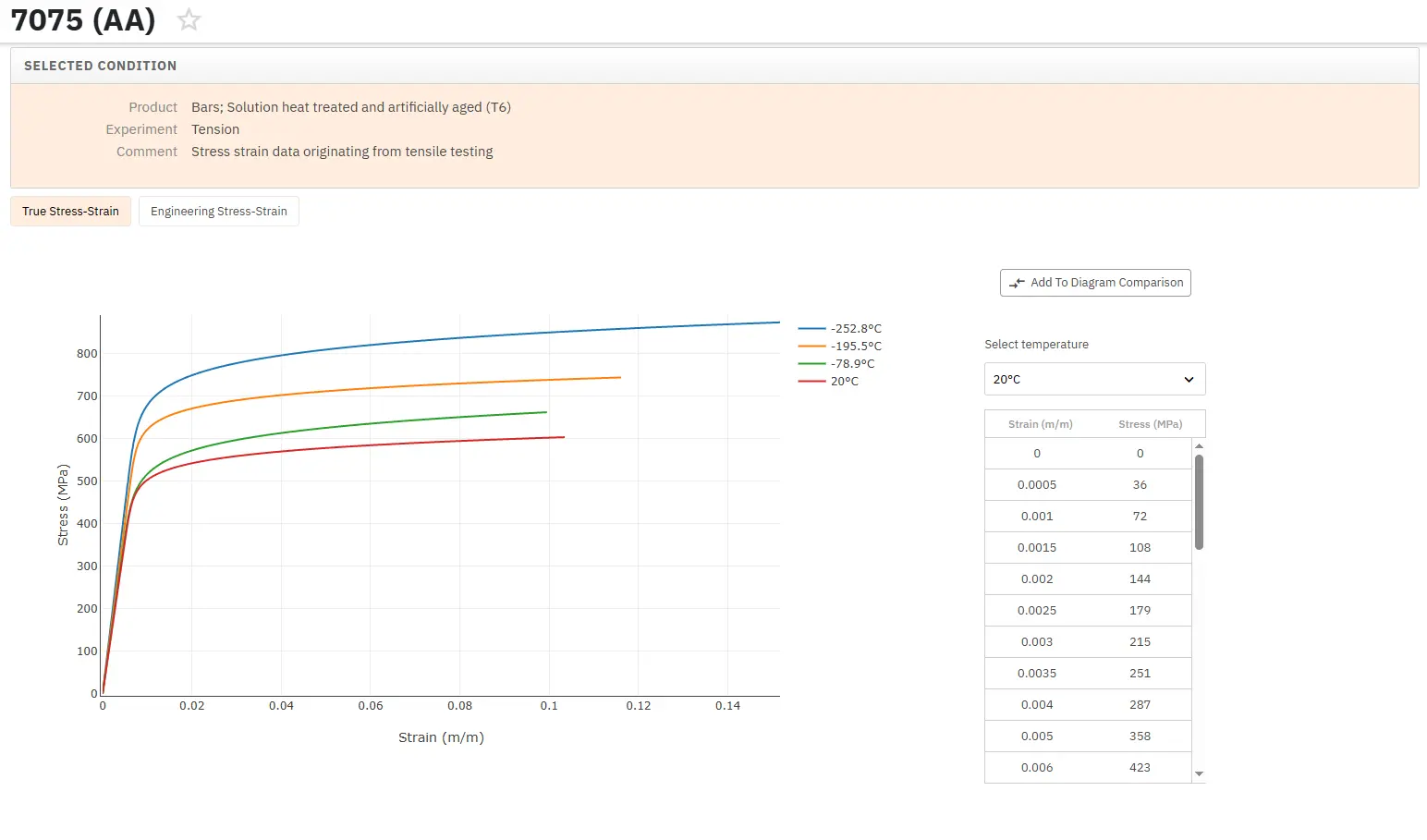

Access Precise Properties of Aluminum Alloys Now!

Total Materia Horizon contains property information for 30,000+ alumiums: composition, mechanical, physical and electrical properties, nonlinear properties and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.