Welding of Reactive and Refractory Metals

Abstract

Reactive and refractory metals present unique welding challenges due to their distinct metallurgical properties. Reactive metals (titanium, zirconium, beryllium) exhibit strong affinity for oxygen and nitrogen at elevated temperatures, forming stable compounds that compromise weld integrity. Refractory metals (tungsten, molybdenum, tantalum, niobium) possess extremely high melting points and similar contamination susceptibilities. Originally developed for aerospace applications, these metals now serve diverse industrial requirements. Successful welding requires meticulous surface preparation, inert atmosphere protection, and specialized techniques including gas tungsten arc welding and electron beam processes. Contamination control is critical, as minor impurities cause embrittlement and raise ductile-brittle transition temperatures. Proper shielding, chemical cleaning, and controlled environments ensure weld quality and structural integrity in these challenging materials.

Introduction to Reactive and Refractory Metals Welding

Reactive metals demonstrate a strong affinity for oxygen and nitrogen at elevated temperatures, forming highly stable compounds upon combination. At lower temperatures, these materials exhibit exceptional corrosion resistance. Refractory metals are characterized by their extremely high melting points and may display similar reactive characteristics.

The refractory metals include tungsten, molybdenum, tantalum, and columbium (niobium), while the reactive metals comprise zirconium, titanium, and beryllium. Originally developed for aerospace industry applications, these materials are increasingly welded for diverse industrial requirements. Due to their shared welding challenges, reactive and refractory metals are commonly grouped together for processing considerations.

Metallurgical Properties and Characteristics

Refractory metals possess extremely high melting points, relatively high density, and excellent thermal conductivity. In contrast, reactive metals feature lower melting points, reduced densities, and, with the exception of zirconium, higher coefficients of thermal expansion.

The growing importance of reactive metals stems from their critical applications in nuclear and space technology. These materials fall within the difficult-to-weld category due to their high affinity for oxygen and other gases at elevated temperatures. This characteristic prevents welding with processes utilizing fluxes or exposing heated metal to atmospheric conditions. Even minor impurity amounts cause these metals to become brittle.

Understanding Ductile-Brittle Transition in Metal Welding

Most reactive and refractory metals exhibit the ductile-brittle transition phenomenon, referring to a specific temperature at which the metal fractures in a brittle manner rather than ductile fashion. Recrystallization during welding can elevate the transition temperature. Contamination during high-temperature periods and impurities can raise the transition temperature sufficiently to render the material brittle at room temperature. Severe contamination that significantly raises the transition temperature can render the weldment worthless.

Gas contamination can occur at temperatures below the metal's melting point, typically ranging from 371°C to 538°C. At room temperature, reactive metals possess an impervious oxide coating that resists further air reaction. However, these oxide coatings melt at temperatures considerably higher than the base metal's melting point, creating processing difficulties. The oxidized coating may enter molten weld metal, creating discontinuities that significantly reduce weld strength and ductility.

Among the three reactive metals, titanium is the most widely used and is routinely welded with appropriate precautions. All refractory metals experience internal contamination or surface erosion when exposed to air at elevated temperatures. Molybdenum exhibits an extremely high oxidation rate at temperatures above 816°C, with tungsten displaying similar behavior. Tantalum and columbium form pentoxides that remain non-volatile below -3.9°C, but provide limited protection due to their non-adherent nature.

Molybdenum and tungsten become embrittled when absorbing minute amounts of oxygen or nitrogen, while columbium and tantalum can withstand larger quantities of these gases. Titanium tolerates significantly more oxygen or nitrogen before embrittlement occurs; however, small hydrogen amounts cause embrittlement. Zirconium can withstand comparable oxygen levels but tolerates much less nitrogen or hydrogen. Beryllium exhibits similar characteristics to zirconium in this regard.

Refractory Metals Welding Techniques

These metals require perfect cleanliness prior to welding and must be welded to prevent air contact with heated material. Chemical cleaning is typically employed, followed by thorough water rinsing to remove all chemical traces from the surface. After cleaning, parts must be protected from reoxidation, best accomplished by storage in inert gas or vacuum chambers.

Molybdenum is welded using gas tungsten arc welding and electron beam processes. Gas metal arc welding can be utilized, but sufficient molybdenum thickness is rarely available to justify this process. While other arc processes have been used for molybdenum welding, results are generally unsatisfactory. Gas shielding process welding is accomplished in inert gas chambers or dry boxes - chambers that can be evacuated and purged with inert gas until all active gases are removed. Welding in pure inert atmosphere typically produces good results.

Filler metal compositions should match the base metal. The heat-affected zone base metal becomes embrittled by grain growth and recrystallization resulting from welding temperatures. Recrystallization raises the transition temperature, causing molybdenum welds to become brittle. Due to molybdenum's high notch sensitivity, craters and notch effects such as undercutting must be avoided. Molybdenum can also be welded using resistance welding processes and diffusion welding.

Tungsten welding follows the same procedures as molybdenum but with intensified challenges. It exhibits greater cracking susceptibility due to higher ductile-to-brittle transition temperatures. Tungsten preparation for welding is more complex. Gas tungsten arc welding uses direct current electrode negative. Welding should proceed slowly to prevent cracking. Preheating may reduce cracking but must occur in inert gas atmosphere.

Commercially pure tantalum is soft and ductile, apparently lacking a ductile-brittle transition. Several commercial tantalum alloys are available. Despite easier welding characteristics, thorough cleaning and inert gas chamber welding produce optimal results. Gas tungsten arc welding is recommended. Powder metallurgy-produced tantalum products may result in weld porosity, while arc cast products do not exhibit porosity. Filler wire is normally unnecessary when welding tantalum, with direct current electrode negative providing best results. High frequency should initiate the arc. Helium is recommended for tantalum welding to provide maximum penetration since joint designs avoid filler metal use.

Several columbium (niobium) alloys are available, with some being ductile and others brittle since the transition temperature approaches room temperature. Gas tungsten arc welding is used for pure columbium and lower strength commercial alloys. Certain alloys can be welded outside inert gas chambers, but special precautions should ensure extremely effective inert gas shielding coverage. Some alloys require preheating for crack-free welding. Electron beam welding is utilized, and columbium can be resistance welded.

Reactive Metals Welding Procedures

Beryllium has been welded using gas tungsten arc welding and gas metal arc welding processes, and is also joined by brazing. Beryllium welding should not be attempted without expert technical assistance. As a toxic metal, beryllium requires extraordinary ventilation and handling precautions.

Zirconium and zirconium-tin alloys are ductile metals that can be prepared using conventional processes. Cleaning is extremely important, with chemical cleaning preferred over mechanical methods. Both gas tungsten arc welding and gas metal arc welding processes join zirconium. Inert gas chambers should maintain efficient gas shielding. Argon or argon-helium mixtures are employed.

Zircalloys are zirconium alloys containing small amounts of tin, iron, and chromium. These alloys can be welded in open environments similarly to titanium. Electron beam and resistance welding processes have been used for zirconium joining.

Titanium Welding: The Key to Success

The secret to successful titanium welding is cleanliness. Small contamination amounts can render titanium welds completely brittle. Contamination from grease, oils, paint, fingerprints, or dirt produces similar effects. Thorough pre-welding cleaning and effective welding protection minimize titanium welding difficulties.

Gas tungsten arc and gas metal arc welding processes can weld titanium. Special procedures must be employed with gas-shielded welding processes, including large gas nozzles and trailing shields to protect the weld face from air. Backing bars providing inert gas shield the weld back from air exposure. Not only molten weld metal, but material heated above 1000°F (approximately 540°C) by welding must be adequately shielded to prevent embrittlement.

When using GTAW processes, thoriated tungsten electrodes should be employed. Electrode size should be the smallest diameter capable of carrying the welding current. Electrodes should be ground to a point and may extend 1.5 times their diameter beyond the nozzle end. Welding uses direct current, electrode negative (straight polarity).

Filler metal selection depends upon the titanium alloys being joined. Pure titanium welding requires pure titanium wire. Titanium alloy welding should employ the next lowest strength alloy as filler wire. Dilution occurring during welding allows the weld deposit to achieve required strength. Similar considerations apply to GMAW titanium welding.

Argon is normally used with gas-shielded processes. Thicker metals require helium or argon-helium mixtures. Welding grade gas purity is satisfactory, requiring a dew point of minus 65°F (minus 54°C). Welding grade shielding gases are generally contamination-free; however, pre-welding tests can be conducted. A simple test involves making a bead on clean titanium scrap and observing its color. The bead should appear shiny, with any surface discoloration indicating contamination.

Extra gas shielding protects heated solid metal adjacent to the weld metal. This shielding is provided by special trailing gas nozzles or chill bars placed immediately next to the weld. Backup gas shielding should protect the weld joint underside. Joint backside protection can also be provided by placing chill bars in intimate contact with backing strips. Sufficiently close contact eliminates backup shielding gas requirements. Critical applications should use inert gas welding chambers, which can be flexible, rigid, or vacuum-purge chambers.

To guarantee weld embrittlement prevention, proper cleaning steps must be implemented. Chlorine-containing solvents should be avoided. Recommended solvents include tri-alcohol or acetone. Titanium can be ground with aluminum oxide or silicon carbide discs. Wet grinding is preferred; however, if wet grinding cannot be used, grinding should proceed slowly to avoid titanium surface overheating.

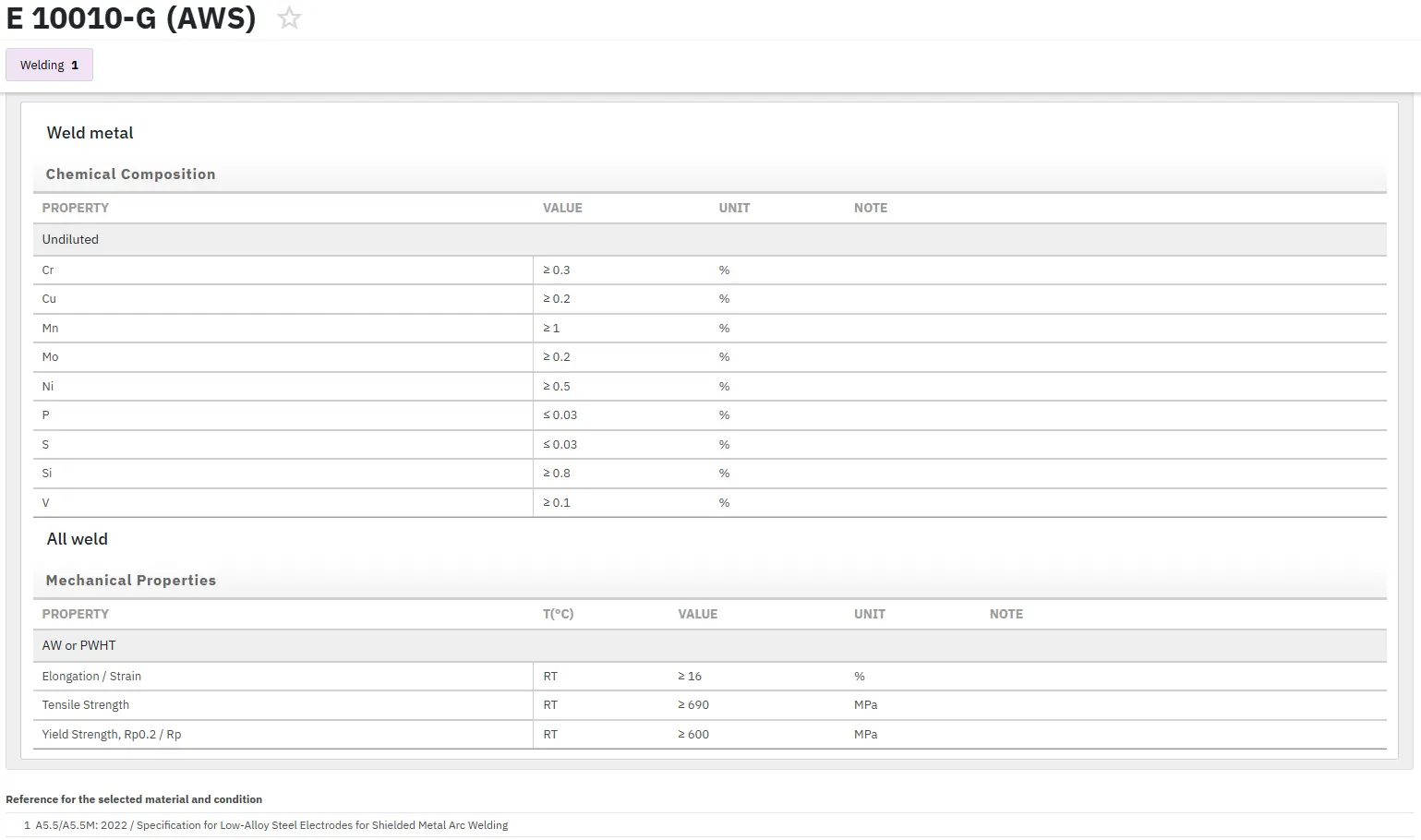

Find Instantly Thousands of Welding Materials!

Total Materia Horizon contains thousands of materials suitable for welding and electrodes, with their properties in bulk and as welded conditions.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.