The Iron-Carbon Equilibrium Diagram

Abstract

The iron-carbon equilibrium diagram forms the foundation for understanding the constitution and structure of all steels and irons. Many fundamental features of this system influence the behavior of even the most complex alloy steels. The phases present in the simple binary Fe-C system persist in more intricate steels, necessitating an understanding of how alloying elements affect these phases. This diagram offers a critical basis for exploring the diverse properties and applications of both plain carbon and alloy steels.

Introduction

The iron-carbon equilibrium diagram represents the metastable equilibrium between iron and iron carbide (cementite). Although cementite is metastable, true equilibrium occurs between iron and graphite. While graphite is prevalent in cast irons (2-4 wt% C), it is challenging to achieve this phase in steels (0.03-1.5 wt% C). Thus, the metastable equilibrium involving iron and cementite is crucial for understanding the practical behavior of most steels.

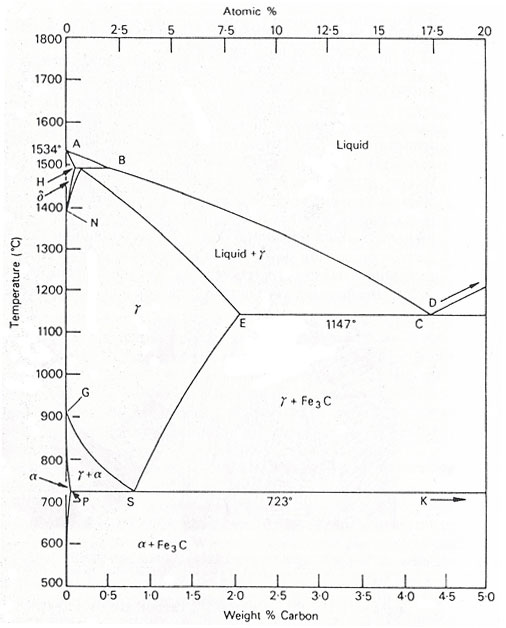

Figure 1. The iron-carbon diagram.

The significantly larger phase field of γ-iron (austenite) compared to α-iron (ferrite) reflects the higher solubility of carbon in γ-iron, peaking at just over 2 wt% at 1147°C (E, Fig. 1). This property is essential in heat treatment, where solution treatment in the γ-region followed by rapid quenching forms a supersaturated solid solution of carbon in iron.

The α-iron phase field is more restricted, with a maximum carbon solubility of 0.02 wt% at 723°C (P). Consequently, α-iron is typically associated with iron carbide across the carbon range found in steels (0.05 to 1.5 wt%). Similarly, the δ-phase field is confined to 1390-1534°C and vanishes entirely at carbon contents above 0.5 wt% (B).

Key Temperatures and Critical Points

Several critical temperatures in the iron-carbon diagram are significant for both theoretical understanding and practical applications:

A1 Temperature: The eutectoid reaction occurs at 723°C (P-S-K) in the binary diagram.

A3 Temperature: Transformation of α-iron to γ-iron occurs at 910°C in pure iron, decreasing progressively along the GS line with increasing carbon.

A4 Temperature: Transition from γ-iron to δ-iron takes place at 1390°C in pure iron but rises with additional carbon.

A2 Temperature: The Curie point, marking the change from ferromagnetic to paramagnetic, occurs at 769°C in pure iron without altering the crystal structure.

The A1, A3, and A4 points can be identified through thermal analysis or dilatometry during cooling and heating cycles. Notably, the Ac and Ar values exhibit sensitivity to heating/cooling rates and alloying elements.

Phase Transformations

The Eutectoid Reaction

The significant difference in carbon solubility between γ- and α-iron typically leads to the rejection of carbon as iron carbide at γ-phase field boundaries. The γ-to-α transformation follows a eutectoid reaction, pivotal in heat treatment. This reaction occurs at 723°C, with a eutectoid composition of 0.80 wt% C. Upon cooling below 723°C, alloys with less than 0.80 wt% C form hypo-eutectoid ferrite, while remaining austenite, enriched to 0.8 wt% C, transforms into pearlite, a lamellar structure of ferrite and cementite.

Alloys with 0.80 to 2.06 wt% C experience initial cementite formation during slow cooling from 1147°C to 723°C, depleting austenite of carbon until it transforms into pearlite at 723°C.

Hypo- and Hyper-Eutectoid Steels

Steels with less than 0.80 wt% carbon (hypo-eutectoid) consist primarily of ferrite and pearlite. As carbon content increases, the pearlite fraction grows, reaching 100% at the eutectoid composition. Above 0.80 wt% carbon, cementite becomes the hyper-eutectoid phase, with a corresponding variation in cementite and pearlite fractions.

Principal Phases

The three principal phases in plain carbon steels—ferrite, cementite, and pearlite—dominate the microstructure when subjected to slow cooling rates, preventing the formation of metastable phases.

The Austenite-Ferrite Transformation

Under equilibrium conditions, pro-eutectoid ferrite forms in alloys with up to 0.8 wt% carbon, occurring at 910°C in pure iron and between 910°C and 723°C in alloys. Quenching from the austenitic state to temperatures below the eutectoid temperature (Ae1) can produce ferrite at temperatures as low as 600°C. Morphological changes arise as transformation temperatures decrease, influencing hypo- and hyper-eutectoid phases. Similar principles apply to cementite formation.

The Austenite-Cementite Transformation

Cementite morphologies, classified by Dube, evolve at progressively lower transformation temperatures. Grain boundary allotriomorphs form initially, followed by side plates or Widmanstätten cementite. Cementite plates exhibit more crystallographic precision due to the complex orientation relationship with austenite.

The Austenite-Pearlite Reaction

Pearlite, a lamellar eutectoid structure, is a prominent microstructural feature of steels, contributing significantly to strength. Discovered over a century ago by Sorby, pearlite forms through diffusion-controlled nucleation and growth. Pearlite nodules nucleate on austenite grain boundaries or inclusions in commercial steels, underscoring their importance in practical applications.

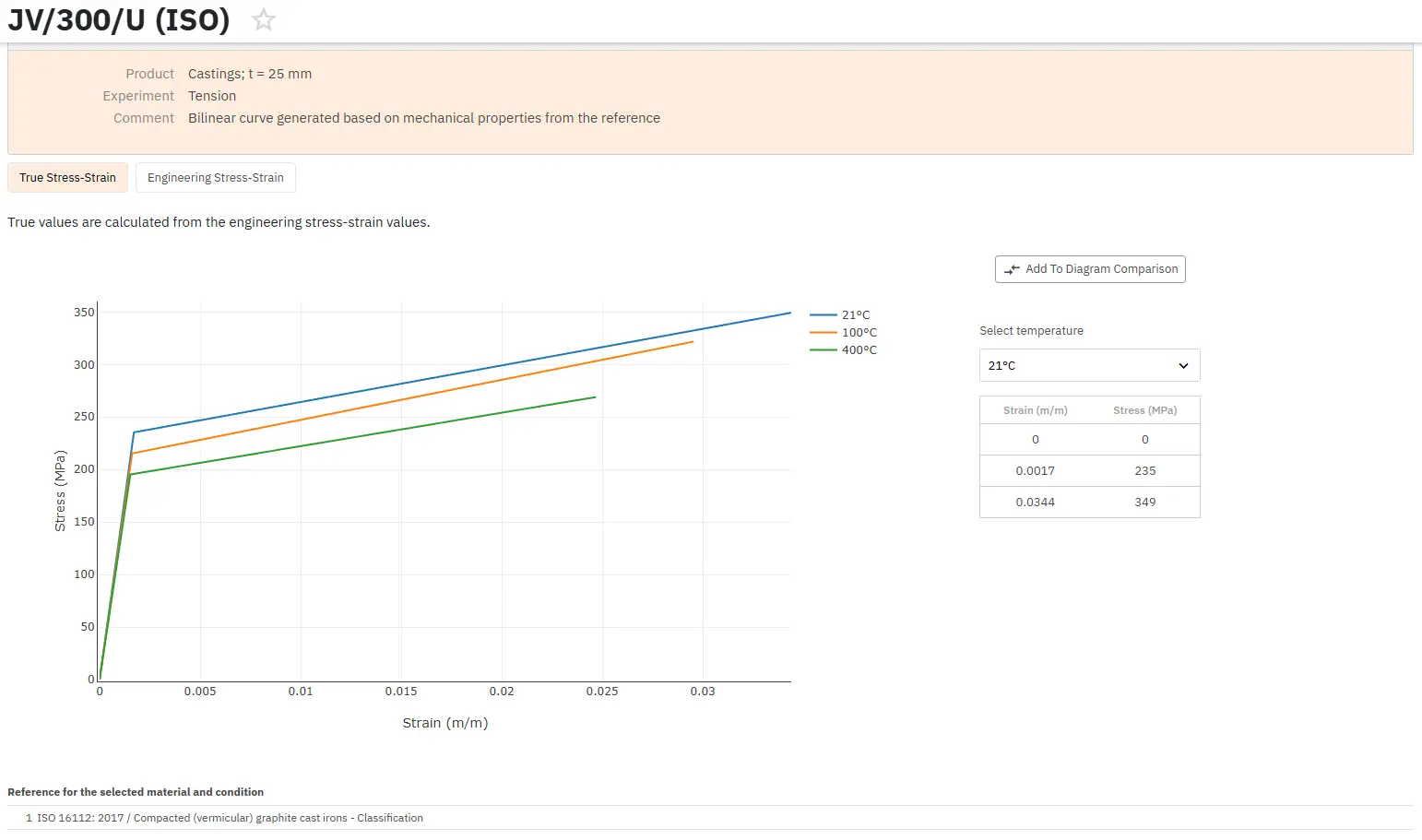

Access Precise Properties of Cast Irons Now!

Total Materia Horizon contains property information for 11,000+ cast irons: composition, mechanical and physical properties, nonlinear properties and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.