Overview of Mechanical Working Processes: Part One

Abstract

Mechanical working processes fundamentally alter metal structure and properties through controlled deformation. During shape change, volume remains constant while dimensions vary proportionally. Deformation elongates grains, creating directional mechanical properties and anisotropic structures. This article examines how mechanical work affects metal structure and macro-properties, followed by process classification. Cold working increases hardness and strength while reducing ductility, with properties varying directionally. Heat treatment of cold-worked metals initiates recrystallization, forming new grain structures. Hot working combines deformation with simultaneous recrystallization, ideally maintaining optimal grain structure throughout processing.

Effects of Mechanical Work on Metal Structure and Properties

During mechanical working processes, the fundamental principle of volume conservation governs all shape changes. When metal undergoes rolling operations, increased length corresponds directly to decreased thickness, maintaining constant mass volume throughout the deformation process.

When deformation forces act upon single-phase grain structures, individual grains elongate systematically. This elongation creates directional mechanical properties, resulting in anisotropic structures where material behavior varies significantly with orientation. The mechanical working processes fundamentally alter the original isotropic characteristics of the base material.

Duplex structures exhibit similar behavior patterns, though with increased complexity. Two distinct phases, designated α and β, respond differently to deformation forces during cold working metals operations. The α phase typically demonstrates soft, ductile characteristics, while the β phase exhibits hard, brittle properties. Consequently, the β phase fractures under stress, creating oriented fragments or stringers aligned longitudinally. This differential response makes duplex structures more anisotropic than single-phase materials.

Extreme deformation degrees produce fibrous structures where individual grains lose their characteristic features due to excessive elongation. This transformation represents the ultimate stage of grain structure deformation under mechanical working processes.

Mechanical Property Changes During Cold Working

Cold working metals significantly affects mechanical properties through systematic changes in material characteristics. Hardness, ultimate tensile strength, and yield stress increase progressively to maximum values, while ductility decreases substantially. Toughness measurements using Izod or Charpy testing methods initially increase with working intensity before gradually declining.

Industrial experience demonstrates that mechanical working processes typically increase hardness and strength by 2.5 to 3 times the original annealed values. This enhancement represents a fundamental advantage of cold working metals in manufacturing applications.

Structural metals exhibit remarkably consistent ductility patterns when measured by percentage elongation. Annealed metals typically achieve approximately 35% elongation, while materials subjected to 80% cold working retain only 2% elongation before tensile failure. This dramatic reduction illustrates the trade-off between strength and ductility in mechanical working processes.

Directional property variations create significant performance differences throughout the worked material. Optimal property combinations typically occur in the longitudinal direction, while the short transverse direction exhibits the poorest characteristics.

Heat Treatment Effects on Cold-Worked Materials

Metal samples subjected to 80% cold working exhibit hard, brittle characteristics with elongated grains and considerable anisotropy. When heated to specific temperatures, new nuclei begin forming within distorted grain structures. This nucleation occurs because thermal energy enables atomic diffusion to stable sites, with required energy levels depending on prior cold working intensity.

Cold working increases internal energy storage within the metal structure. Greater cold working degrees result in higher residual internal energy, requiring less thermal energy to initiate nucleation in heavily worked materials compared to lightly worked specimens.

Understanding nucleation mechanisms and controlling factors for nuclei formation proves crucial for optimizing recrystallization temperature processes. Nucleation preferentially occurs in regions with highest residual stresses, typically found at multiple boundary intersections where grain structure deformation creates maximum distortion.

Extended exposure at nucleating temperatures allows increased atomic diffusion to nuclei sites, with atoms occupying minimum energy positions. Growth volumes around each nucleus expand to visible dimensions until interference between adjacent growth regions prevents further expansion. These growth volumes become new grains, with interstititial distorted zones forming grain boundaries.

Recrystallization and Grain Growth Phenomena

Recrystallized grains demonstrate softer characteristics and larger dimensions than worked grains, with random atomic orientation between grains replacing the forced orientation typical of worked materials. Each nucleus develops into one grain, determining final recrystallized grain size through this one-to-one relationship.

Greater cold working degrees produce smaller recrystallized grain sizes due to increased nucleation sites. Without cold working, no high-stress centers exist, preventing recrystallization during heating. Critical cold working amounts create few nucleation sites that grow excessively, producing very large grains.

Continued exposure at recrystallization temperature after complete recrystallization enables ongoing atomic diffusion, causing some grains to grow at others' expense. This grain growth phenomenon commonly occurs in industrial processes, resulting in final annealed grain sizes much coarser than initial recrystallized dimensions.

Grain growth operates through diffusion processes affected by time and temperature variables. While diffusion maintains linear time relationships, temperature increases create exponential rate effects. Each 10°C temperature increase doubles diffusion rates, making temperature control critical for managing final grain structure.

Industrial Considerations for Grain Size Control

Final grain size after cold working and annealing significantly impacts industrial process outcomes. Excessively coarse grains produce rough surface finishes during machining and create "orange peel" effects after pressing operations. Grain size also directly influences material toughness characteristics.

Optimal structures for subsequent working consist of small, uniform equiaxed grains that provide consistent material behavior. The most critical factor in industrial mechanical working processes involves controlling final furnace temperatures. These temperatures should remain as low as possible while ensuring complete recrystallization within acceptable time frames.

Hot Working Process Fundamentals

Hot working of metals can be conceptualized as simultaneous cold working and annealing at elevated temperatures above the recrystallization temperature. This process combines grain deformation with instantaneous recrystallization, theoretically eliminating deformation effects on structure and properties immediately.

However, practical hot working applications face timing constraints. While deformation effects occur instantaneously, recrystallization requires finite time periods. Unless hot working steel processes operate slowly enough to permit complete recrystallization, evidence of working persists after process completion.

This understanding provides precise definitions for hot and cold working classifications. Hot working occurs at temperatures and strain rates allowing recrystallization to match deformation pace. Cold working operates under conditions where recrystallization cannot keep pace with deformation rates.

Hot Rolling Applications in Steel Processing

Hot working steel strip for deep drawing applications exemplifies these principles in industrial practice. Final materials should consist of small equiaxed grains exhibiting minimal mechanical anisotropy for optimal forming characteristics.

Steel's dual-phase structure, comprising ferrite and cementite, creates unique challenges due to different recrystallization temperature requirements. Ferrite recrystallizes around 600°C, while cementite requires temperatures between 700°C and 900°C, varying with carbon content.

Even when ferrite recrystallizes after hot working, oriented cementite formation prevents equiaxed grain development, maintaining mechanical anisotropy and creating "pancaked" grain structures. Two primary precautions address this challenge: limiting carbon content to 0.1% maximum to reduce second-phase amounts, and controlling second-phase morphology to minimize detrimental effects.

Cementite morphology varies with cooling conditions and finishing temperatures. Massive forms appear on ferrite grain boundaries with very slow cooling or high finishing temperatures. Lamellar forms (pearlite) result from intermediate cooling rates and relatively high finishing temperatures. Fine dispersed spheroids develop with optimum cooling rates achieved through relatively low hot working temperatures, providing the most favorable structure for subsequent processing.

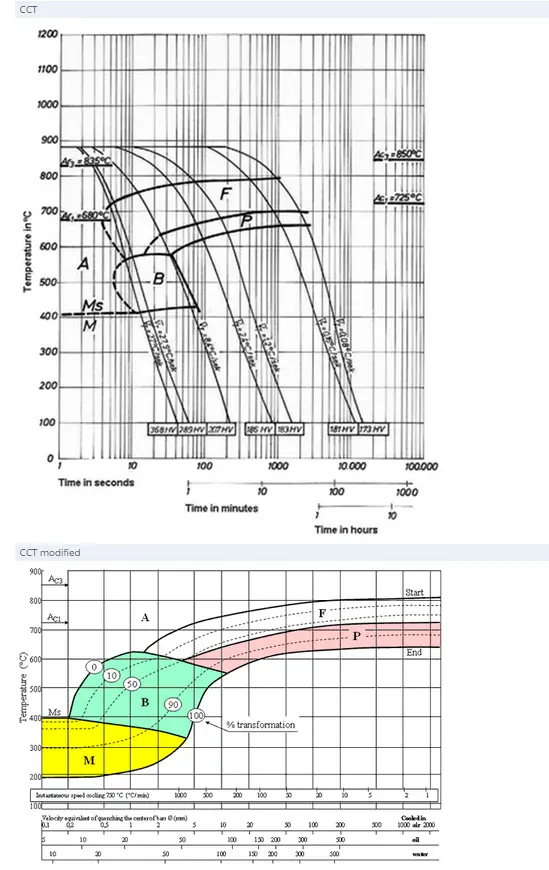

Find Instantly Thousands of Heat Treatment Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains heat treatment details for hundreds of thousands of materials, hardenability diagrams, hardness tempering, TTT and CCT diagrams, and much more.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.