Metallography: Part Three

Abstract

The purpose of the coarse grinding stage is to generate the initial flat surface necessary for the subsequent grinding and polishing steps. As a result of sectioning and grinding, the material may get cold worked to a considerable depth with a resultant transition zone of deformed material between the surface and the undistorted metal.

Each stage of metallographic sample preparation must be carefully performed; the entire process is designed to produce a scratch free surface by employing a series of successively finer abrasives.

Coarse Grinding

In view of the perfection required in an ideally prepared metallographic sample, it is essential that each preparation stage be carefully performed. The specimen must:

1. Be free from scratches, stains and others imperfections which tend to mark the surface.

2. Retain non-metallic inclusions.

3. Reveal no evidence of chipping due to brittle intermetallic compounds and phases.

4. Be free from all traces of disturbed metal.

The purpose of the coarse grinding stage is to generate the initial flat surface necessary for the subsequent grinding and polishing steps. As a result of sectioning and grinding, the material may get cold worked to a considerable depth with a resultant transition zone of deformed material between the surface and the undistorted metal. Course grinding can be accomplished either wet or dry using 80 to 180 grit electrically powered disks or belts, but care must be taken to avoid significant heating of the sample. The final objective is to obtain a flat surface free from all previous tool marks and cold working due to specimen cutting.

Medium and Fine Grinding

Medium and Fine Grinding of metallurgical samples are closely allied with the Coarse Grinding which precedes them. Each stage of metallographic sample preparation must be carefully performed; the entire process is designed to produce a scratch free surface by employing a series of successively finer abrasives. Failure to be careful in any stage will result in an unsatisfactory sample.

Manual Grinding

The manual method is useful when automatic equipment is not available or when the depth of grinding is critical. Cross sections of microelectronic devices, such as multiplayer packages, often must be ground to a specific depth.

Figure 1: Automatic grinding and polishing machine

The following are the most common metallographic abrasives:

Silicon Carbide - SiC is a manufactured abrasive produced by a high temperature reaction between silica and carbon. It has a hexagonal-rhombohedral crystal structure and has a hardness of approximately 2500 HV. It is an ideal abrasive for cutting and grinding because of its hardness and sharp edges. It is also somewhat brittle, and therefore it cleaves easily to produce sharp new edges (self sharpening). SiC is an excellent abrasive for maximizing cutting rates while minimizing surface and subsurface damage. For metallographic preparation, SiC abrasives are used in abrasive blades and for coated abrasive grinding papers ranging from very coarse 60 grit to very fine 1200 grit sizes.

Bonded or coated abrasive papers of SiC are designed so that the abrasive will have a large number of cutting points (negative abrasive rank angle). This is achieved by aligning the abrasive particles approximately normal to the backing. Note that coated abrasives are not quite coplanar, thus SiC papers produce the maximum efficiency (cut rate, stock removal and minimal damage) because new abrasive is exposed as the old abrasive breaks down.

Alumina - Alumina is a naturally occurring material (Bauxite). It exits in either the softer gamma (mohs 8) or harder alpha (mohs 9, 2000 HV) phase. Alumina abrasives are used primarily as a final polishing abrasive because of their high hardness and durability. Unlike SiC, alumina breaks down relatively easily to submicron or colloidal particles (Fine Abrasives).

Note that larger coated or bonded grit sizes of alumina are commercially available, however they are not ideal for metallographic applications because they become dull, resulting in lower cut rates and higher surface and subsurface damage.

Diamond - Is the hardest material known to man (mohs 10, 8000 HV). It has a cubic crystal structure, and is available as a natural or an artificial product. Although diamond would be ideal for coarse grinding, its price makes it a very inefficient grinding material for anything except for hard ceramics. For metallographic applications, polycrystalline diamond is recommended as a rough polishing abrasive (PC diamond).

Grinding Parameters

Successful grinding is also a function of the following parameters:

Grinding Pressure

Relative Velocities

Grinding Direction

| Symptom | Cause | Action |

| Uneven grinding across the specimen and mount | *Improper tracking of specimen over abrasive paper *Unequal head/base speeds |

*Orient specimen in holder so that the hardest portion of the specimen/mount tracks over the entire abrasive paper (uniform degradation of paper) *Match the head and base speed and rotate in the same direction. Grinding at 200/200 spm and polishing at 100/100spm |

| Excessive vibration in machine | *Too high a load or too low a speed *Inadequate machine design *Improper lubricant Unequal head/base speeds |

*Reduce initial grinding force or increase grinding speed *Check with equipment vendor for equipment upgrades *Increase lubricant flow and/or use a water soluble lubricant *Match the head and base speed and rotate in the same direction. Grinding at 200/200spm and polishing 100/100spm |

| Embedding of fractured abrasive grains | *Common in the grinding of very soft materials *Unequal head/base speeds |

*Use alumina grinding papers vs. SiC papers *Match the head and base speed and rotate in the same direction. Grinding at 200/200spm and polishing at 100/100spm |

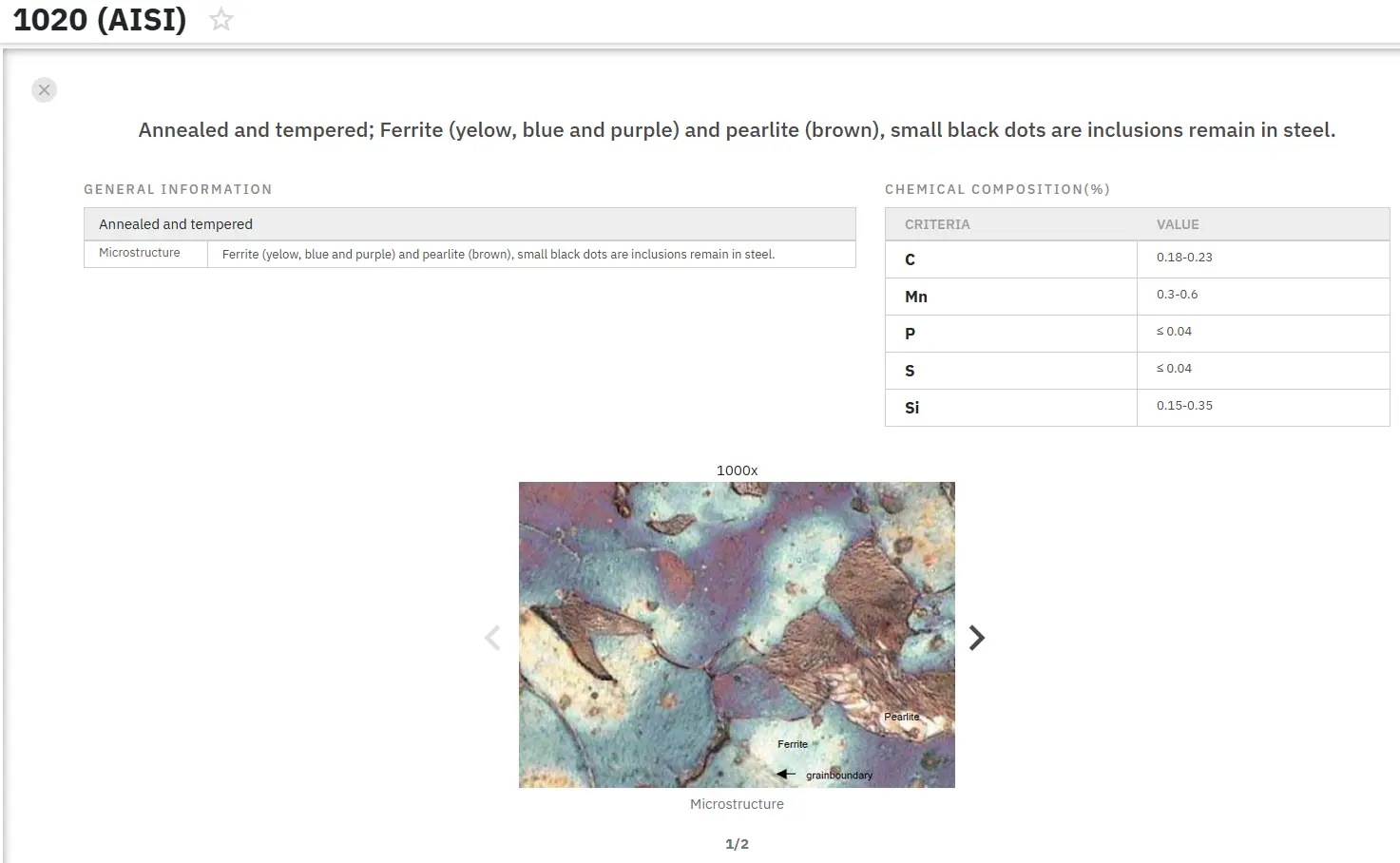

Find Instantly Thousands of Metallography Diagrams!

Total Materia Horizon contains a unique collection of metallography images across a large range of metallic alloys, countries, standards and heat treatments.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.