Macroscopic Aspects of Fracture

Abstract

Fracture can be viewed on many levels, depending on the size of the fractured region that is of interest. At the macroscopic level fracture occurs over dimensions that are of the order of the size of flaws or notches (1 mm or greater).

From the principles of fracture mechanics it is possible to determine macroscopic fracture criteria in terms of the nominal fracture strength, the flaw length, and the critical amount of plastic work required to initiate unstable fracture -- the fracture toughness.

Fracture is an inhomogeneous process of deformation that makes regions of material to separate and load-carrying capacity to decrease to zero. It can be viewed on many levels, depending on the size of the fractured region that is of interest. At the atomistic level fracture occurs over regions whose dimensions are of the order of the atomic spacing (10-7 mm); at the microscopic level fracture occurs over regions whose dimensions are of the order of the grain size (about 10-3 mm); and at the macroscopic level fracture occurs over dimensions that are of the order of the size of flaws or notches (1 mm or greater).

At each level there are one or more criteria that describe the conditions under which fracture can occur. For example, at the atomistic level fracture occurs when bonds between atoms are broken across a fracture plane and new crack surface is created. This can occur by breaking bonds perpendicular to the fracture plane, a process called cleavage, or by shearing bonds across the fracture plane, a process called shear. At this level the fracture criteria are simple; fracture occurs when the local stresses build up either to the theoretical cohesive strength σc ≈ E/10 or to the theoretical shear strength τc ≈ G/10, where E and G are the respective elastic and shear module.

The high stresses required to break atomic bonds are concentrated at the edges of inhomogeneities that are called micro cracks or macro cracks (flaws, notches, cracks). At the microscopic and macroscopic levels fracture results from the passage of a crack through a region of material. The type of fracture that occurs is characterized by the type of crack responsible for the fracture.

Few structural materials are completely elastic; localized plastic strain usually precedes fracture, even when the gross fracture strength is less than the gross yield strength. Fracture in these instances is initiated when a critical amount of local plastic strain or plastic work occurs at the tin of a flaw.

From the principles of fracture mechanics it is possible to determine macroscopic fracture criteria in terms of the nominal fracture strength, the flaw length, and the critical amount of plastic work required to initiate unstable fracture -- the fracture toughness.

Types of Fracture That Occur Under Uniaxial Tensile Loading

Cleavage fractures occur when a cleavage crack spreads through a solid under a tensile component of the externally applied stress. The material fractures because the concentrated tensile stresses at the crack tip are able to break atomic bonds. In many crystalline materials certain crystallographic planes of atoms are most easily separated by this process and these are called cleavage planes.Under uniaxial tensile loading the crack tends to propagate perpendicularly to the tensile axis. When viewed in profile, cleavage fractures appear "flat" or "square", and these terms are used to describe them.

Most structural materials are polycrystalline. The orientation of the cleavage plane(s) in each grain of the aggregate is usually not perpendicular to the applied stress so that, on a microscopic scale, the fractures are not completely flat over distances larger than the grain size.

In very brittle materials cleavage fractures can propagate continuously from one grain to the next. However, in materials such as mild steel the macroscopic cleavage fracture is actually discontinuous on a microscopic level; most of the grains fracture by cleavage but some of them fail in shear, causing the cleaved grains to link together by tearing.

Shear fracture, which occurs by the shearing of atomic bonds, is actually a process of extremely localized (inhomogeneous) plastic deformation. In crystalline solids, plastic deformation tends to be confined to crystallographic planes of atoms which have a low resistance to shear. Shear fracture in pure single crystals occurs when the two halves of the crystal slip apart on the crystallographic glide planes that have the largest amount of shear stress resolved across them. When the shear occurs on only one set of parallel planes, a slant fracture is formed.

In polycrystalline materials the advancing shear crack tends to follow the path of maximum resolved shear stress. This path is determined by both the applied stress system and the presence of internal stress concentrators such as voids, which are formed at the interface between impurity particles (e.g., nonmetallic inclusions) and the matrix material. Crack growth takes place by the formation of voids and their subsequent coalescence by localized plastic strains.

Shear fracture in thick plates and round tensile bars of structural materials begins in the center of the structure (necked region) and spreads outwards. The macroscopic fracture path is perpendicular to the tensile axis. On a microscopic scale the fracture is quite jagged, since the crack advances by shear failure (void coalescence) on alternating planes inclined at 30-45° to the tensile axis.

This form of fracture is commonly labeled normal rupture (since the fracture path is normal to the tensile axis) or fibrous fracture (since the jagged fracture surface has a fibrous or silky appearance). Normal rupture forms the central (flat) region of the familiar cup-cone pattern. The structure finally fails by shear rupture (shear lip formation) on planes inclined at 45° to the tensile axis. This form of fracture is less jagged, appears smoother, and occurs more rapidly than the normal rupture which precedes it. Similarly noncleavage fracture in thin sheets of engineering materials occurs exclusively by shear rupture and the fracture profile appears similar to the slant fracture.

Under certain conditions the boundary between adjacent grains in the poly-crystalline aggregate is weaker than the fracture planes in the grains themselves. Fracture then occurs intergranularly, by one of the processes mentioned above, rather than through the grains (transgranular fracture). Thus there are six possible modes of fracture: transgranular cleavage, transgranular shear rupture, transgranular normal rupture, and intergranular cleavage, intergranular shear rupture, intergranular normal rupture.

Fracture takes place by that mode which requires the least amount of local strain at the tip of the advancing crack. Both the environmental fracture exclusively by one particular mode over a large variety of conditions and the state of applied (nominal) stress mid strain determine the type of fracture which occurs, and only a few materials and structures operating conditions (i.e., service temperature, corrosive environment, and so on).

Furthermore, under any given condition more than one mode of fracture can cause failure of a structural member and the fracture is described as "mixed". This implies that the relative ease of one type of crack propagation can change, with respect to another type, as the overall fracture process lakes place. For example, normal rupture, cleavage, and shear rupture are all observed on the fracture surfaces of notched mild steel specimens broken in impact at room temperature.

In order to analyze the fracture process under various types of stress systems, it is necessary to establish a coordinate system with respect to both the fracture plane, the direction of crack propagation, and the applied stress system.

One of the difficulties encountered by engineers and scientists who are interested in a particular aspect of the fracture problem is the large mass of notation and coordinate systems used by other workers who have investigated similar problems.

Three distinct modes of separation at the crack tip can occur:

- Mode I -- The tensile component of stress is applied in the y direction, normal to the faces of the crack, either under plane-strain (thick plate, t large) or plane-stress (thin plate, t small) conditions.

- Mode II -- The shear component of stress is applied normal to the leading edge of the crack either under plane-strain or plane-stress conditions.

- Mode III -- The shear component of stress is applied parallel to the leading edge of the crack (antiplane strain).

Summary

- Fracture is an inhomogeneous form of deformation which can be viewed on different levels. On an atomistic level it occurs by the breaking of atomic bonds, either perpendicular to a plane (cleavage) or across a plane (shear). On a microscopic level cleavage occurs by the formation and propagation of microcracks and the separation of grains along cleavage planes. Shear fracture (rupture) usually occurs by the formation of voids within grains and the separation of material between the voids by intense shear.

On a macroscopic level cleavage occurs when a cleavage crack spreads essentially perpendicular to the axis of maximum tensile stress. Shear fracture occurs when a fibrous crack advances essentially perpendicular to the axis of maximum tensile stress (normal rupture) or along a plane of maximum shear stress (shear rupture).

Fracture is said to be transgranular when microcrack propagation and void coalescence occur through the grains and intergranular when they occur along grain boundaries. More than one mode of crack propagation can contribute to the fracture of a structure. In general, cleavage fracture is favored by low temperatures.

- Fracture occurs in a perfectly elastic solid when the stress level at the tip of a preinduced flaw reaches the theoretical cohesive stress E/10 and a sufficient amount of work γs is done to break atomic bonds and create free surface.

- When the yield stress of a material is less than E/10 (i.e., in a ductile material or in the vicinity of a stopped crack in a partially brittle one), plastic flow occurs near the crack tip and the stress level in the plastic zone is less than E/10. Consequently the crack cannot advance directly as an elastic Griffith crack.

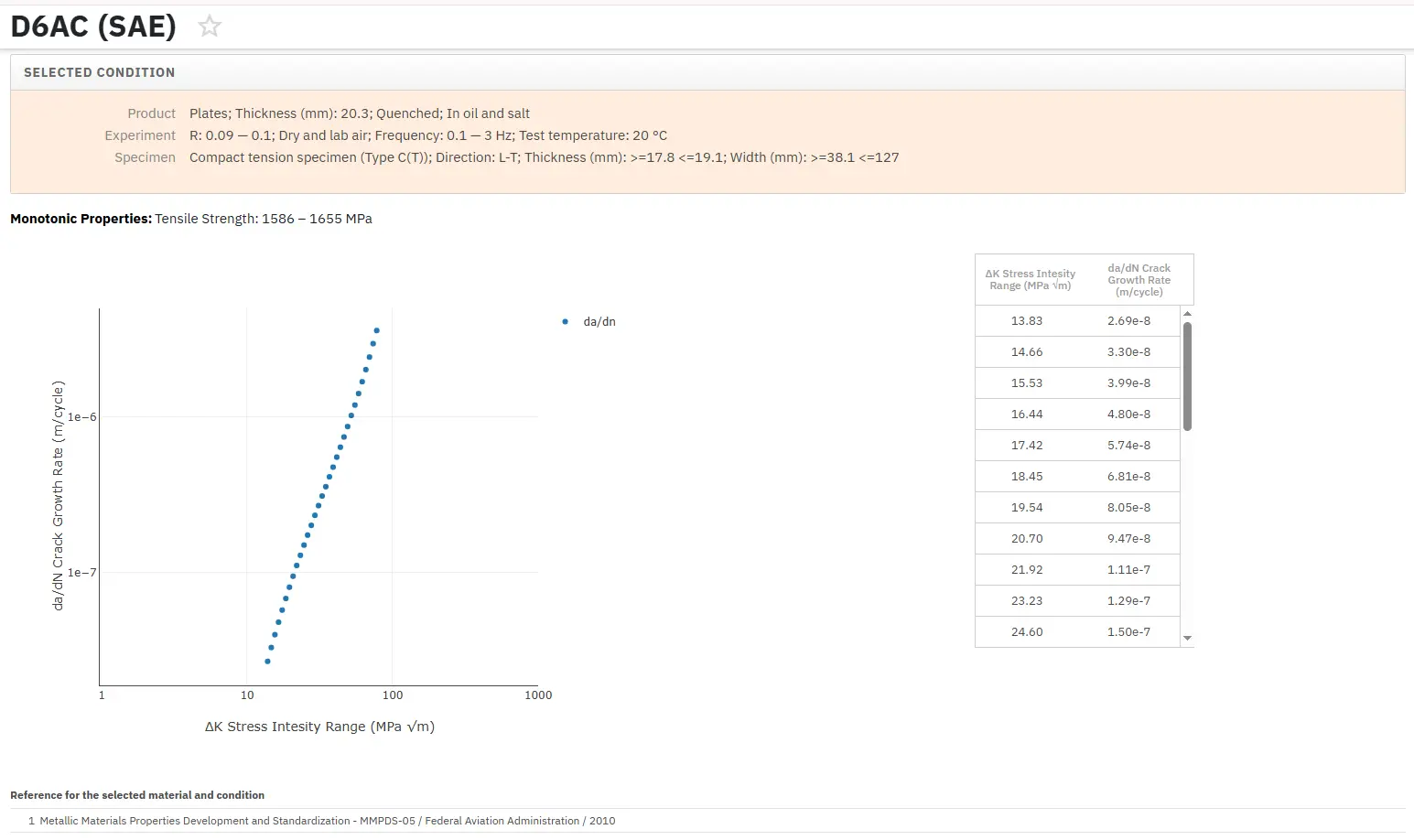

Access Fracture Mechanics Properties of Thousands of Materials Now!

Total Materia Horizon includes a unique collection of fracture mechanics properties such as K1C, KC, crack growth and Paris law parameters, for thousands of metal alloys and heat treatments.

Get a FREE test account at Total Materia Horizon and join a community of over 500,000 users from more than 120 countries.