The Strengthening of Iron and Steel

Abstract

Although pure iron exhibits weak mechanical properties, steels demonstrate remarkable versatility across the strength spectrum, ranging from low yield stress levels around 200 MPa to exceptionally high levels approaching 2000 MPa. These diverse mechanical properties result from the strategic combination of multiple strengthening mechanisms, though quantifying individual contributions in complex steel systems remains challenging. Iron strengthening occurs through several fundamental mechanisms: work hardening, solid solution strengthening by interstitial and substitutional atoms, grain size refinement, and dispersion strengthening including lamellar and randomly dispersed structures. The distinctive role of interstitial solutes, particularly carbon and nitrogen, sets iron apart through their interactions with dislocations and preferential combination with metallic alloying elements, enabling precise control over steel microstructure and mechanical properties.

Work Hardening in Steel Systems

Work hardening represents a crucial strengthening process in steel manufacturing, particularly for achieving high strength levels in rod and wire products across both plain carbon and alloy steel compositions. The effectiveness of this mechanism becomes evident when examining practical applications: a 0.05% carbon steel subjected to 95% reduction in area through wire drawing experiences a tensile strength increase of 550 MPa, while higher carbon steels can achieve strength improvements up to twice this magnitude. This phenomenon enables plain carbon steels to reach strength levels exceeding 1500 MPa without requiring specialized alloying elements.

Fundamental research on iron deformation has primarily focused on pure single crystals and polycrystals under controlled small deformations. The diversity of available slip planes creates irregular wavy slip bands in deformed crystals, as dislocations readily transition between different plane types through cross slip when sharing common slip directions.

The yield stress of iron single crystals demonstrates significant sensitivity to both temperature and strain rate variations, with similar dependencies observed in less pure polycrystalline iron. This temperature sensitivity cannot be attributed solely to interstitial impurities but rather reflects the temperature's effect on the Peierls-Nabarro stress required for free dislocation movement within the crystal structure.

Solid Solution Strengthening Through Interstitial Elements

The formation of interstitial atmospheres at dislocations requires solute diffusion processes. Since carbon and nitrogen diffuse significantly more rapidly in iron compared to substitutional solutes, strain aging readily occurs within the temperature range of 20°C to 150°C. Under these conditions, the atmosphere condenses to form organized rows of interstitial atoms along dislocation cores.

This phenomenon occurs because elevated temperatures enable interstitial atom diffusion during deformation, facilitating atmosphere formation around dislocations generated throughout the stress-strain curve. Steels tested under these conditions exhibit reduced ductility due to high dislocation density and carbide particle nucleation on dislocations where carbon concentration peaks. This behavior is commonly termed "blue brittleness," referencing the characteristic interference color of steel surfaces when oxidized within this temperature range.

The mechanism of dislocation breakaway from carbon atmospheres as a cause of sharp yield points became controversial when researchers discovered that providing free dislocations through surface scratching did not eliminate the sharp yield point phenomenon. An alternative theory emerged, proposing that once condensed carbon atmospheres form in iron, dislocations remain locked, and yield phenomena result from the generation and movement of newly formed dislocations.

The occurrence of sharp yield points depends fundamentally on sudden increases in mobile dislocation numbers. However, the specific mechanism varies with the effectiveness of pre-existing dislocation locking. Weak pinning results in yield points through unpinning processes, while strong locking by interstitial atmospheres or precipitates causes yield points through rapid new dislocation generation.

High Interstitial Concentration Strengthening

Austenite can accommodate up to 10% carbon in solid solution, which rapid quenching can retain. Under these circumstances, phase transformation occurs not to ferrite but to a tetragonal structure called martensite. This phase forms through diffusionless shear transformation, creating characteristic lath or plate morphologies.

Sufficiently rapid quenching produces martensite as essentially a supersaturated solid solution of carbon in a tetragonal iron matrix. Since carbon concentration can greatly exceed equilibrium ferrite concentrations, strength increases substantially. High carbon martensites typically exhibit exceptional hardness but limited ductility, with yield strengths reaching 1500 MPa. This strength increase derives primarily from enhanced interstitial solid solution hardening, supplemented by contributions from the high dislocation density characteristic of martensitic transformations in iron-carbon alloys.

Substitutional Solid Solution Strengthening

Many metallic elements form substitutional solid solutions in both γ-iron and α-iron phases. For constant atomic concentrations of alloying elements, significant strength variations occur. Single crystal data reveals that vanadium provides weak strengthening effects on α-iron at low concentrations below 2%, while silicon and molybdenum demonstrate superior strengthening effectiveness. Additional research indicates that phosphorus, manganese, nickel, and copper also function as effective strengtheners, though relative strengthening effects may vary with testing temperature and interstitial solute concentrations.

Figure 1: Solid solution strengthening of iron crystals by substitutional solutes. Ratio of the critical resolved shear stress τ0 to shear modulus μ as a function of atomic concentration.

Substitutional solute atom strengthening generally increases with larger atomic size differences from iron, following the Hume-Rothery size effect. However, research by Fleischer and Takeuchi demonstrates that elastic behavior differences between solute and solvent atoms significantly influence overall strengthening achievement.

In practical applications, solid solution strengthening contributions superimpose on hardening from other sources, including grain size effects and dispersions. This strengthening increment, similar to grain size effects, need not adversely impact ductility. In industrial steels, solid solution strengthening represents a significant factor in overall strength, achieved through familiar alloying elements such as manganese, silicon, nickel, and molybdenum. These elements frequently coexist in particular steel compositions with additive effects. Since these alloying elements serve other purposes—silicon for deoxidation, manganese for sulfur combination, or molybdenum for hardenability promotion—solid solution hardening contributions provide valuable additional benefits.

Grain Size Refinement Effects

Ferrite grain size refinement provides one of the most important strengthening routes in steel heat treatment. The grain size effect on yield stress can be explained by assuming dislocation sources operate within crystals, causing dislocations to move and eventually pile up at grain boundaries. These pile-ups generate stress in adjacent grains, which, upon reaching critical values, activate new sources in neighboring grains.

This process propagates the yielding mechanism from grain to grain. Grain size determines the distance dislocations must travel to form grain boundary pile-ups and thus the number of dislocations involved. Large grain sizes produce pile-ups containing greater dislocation numbers, generating higher stress concentrations in neighboring grains.

Practically, finer grain sizes produce higher resulting yield stresses, making final ferrite grain size a critical consideration in modern steelmaking. While coarse grain sizes with d-1/2= 2 (d = 0.25 mm) yield approximately 100 MPa in mild steels, grain refinement to d-1/2= 20 (d = 0.0025 mm) raises yield stress above 500 MPa. Achieving grain sizes in the 2-10 μm range provides extremely valuable strength improvements.

Dispersion Strengthening Mechanisms

All steels typically contain multiple phases, with several phases often recognizable in microstructural analysis. The matrix, usually ferrite (bcc structure) or austenite (fcc structure) strengthened through grain size refinement and solid solution additions, receives further strengthening through controlled dispersions of other microstructural phases. The most common secondary phases are carbides formed due to carbon's low solubility in α-iron.

In plain carbon steels, this carbide is typically Fe3C (cementite), occurring in diverse structures ranging from coarse lamellar forms (pearlite) to fine rod or spheroidal precipitates (tempered steels). Alloy steels exhibit similar structural ranges, except iron carbide is often replaced by thermodynamically more stable carbides. Other dispersed phases include nitrides, intermetallic compounds, and in cast irons, graphite.

Most dispersions contribute to strengthening but may adversely affect ductility and toughness. Fine dispersions, ideally consisting of small spheres randomly distributed in a matrix, exhibit well-defined relationships between yield stress or initial flow stress and dispersion parameters.

These relationships apply to simple dispersions sometimes found in steels, particularly after tempering when plain carbon steel structures consist of spheroidal cementite particles in ferritic matrices. They provide approximations for less ideal cases common in steels, where dispersions vary from fine rods and plates to irregular polyhedra. The most familiar steel structure is eutectoid pearlite, typically a lamellar ferrite and cementite mixture representing an extreme dispersion form that provides valuable strengthening contributions.

Comprehensive Strengthening Overview

Steel strength arises from multiple phenomena that collectively contribute to observed mechanical properties. Steel heat treatment aims to adjust these contributions for achieving required mechanical property balance. The γ/α phase transformation enables significant microstructural variations, producing wide-ranging mechanical properties even in plain carbon steels. Additional metallic alloying elements, primarily through their transformation influence, provide enhanced microstructural control with consequent mechanical property benefits.

The strategic combination of work hardening, solid solution strengthening, grain size refinement, and dispersion strengthening mechanisms allows metallurgists to tailor steel properties for specific applications. Understanding these individual contributions and their interactions remains essential for developing advanced steel grades that meet increasingly demanding performance requirements across diverse industrial applications.

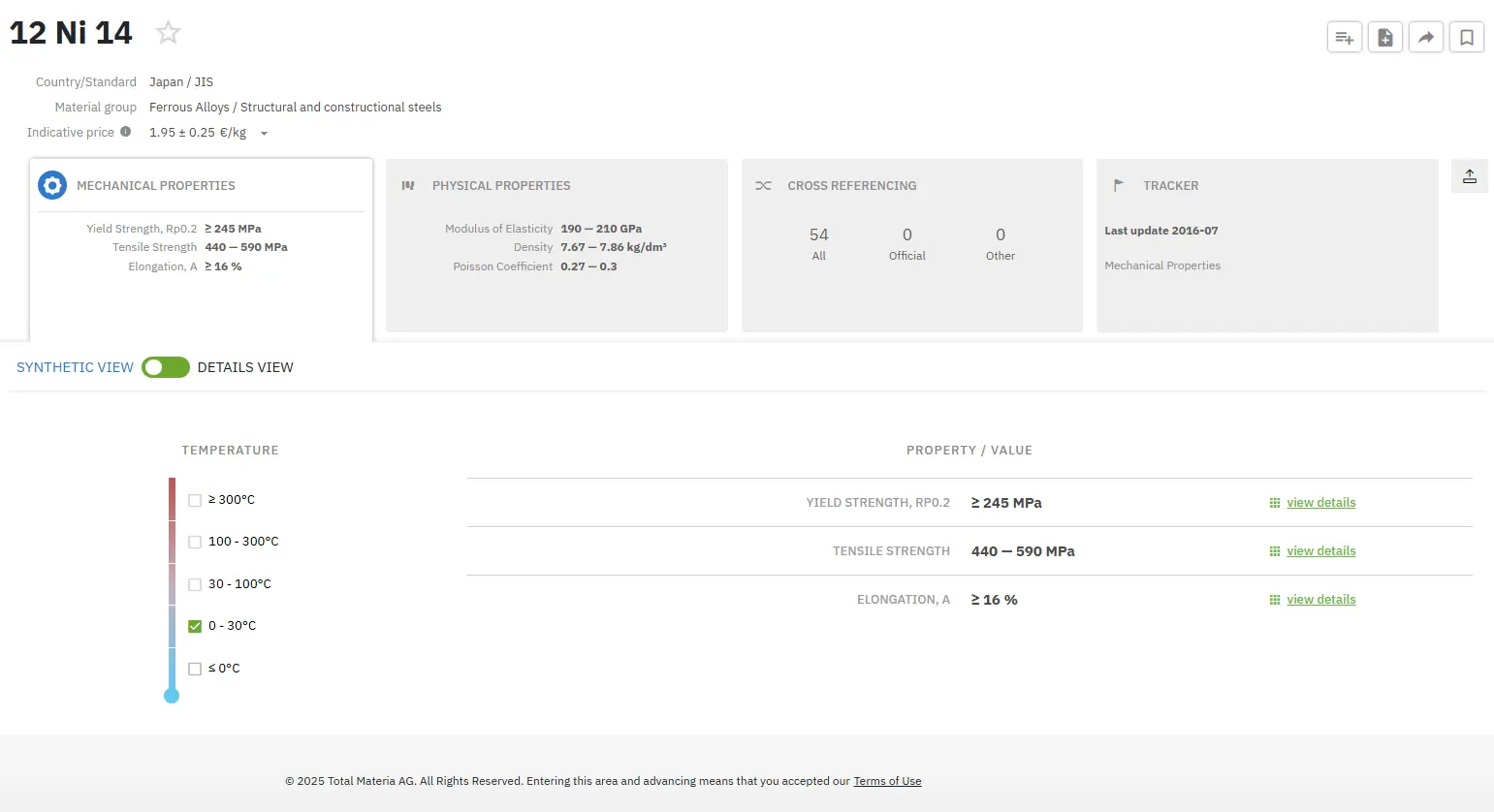

Accédez en quelques instants à des propriétés mécaniques précises !

Total Materia Horizon contient les propriétés mécaniques et physiques de centaines de milliers de matériaux, à différentes températures, formes de livraison, conditions métallurgiques, et bien plus.

Profitez d’un compte d’évaluation GRATUIT sur Total Materia Horizon et rejoignez notre communauté qui compte plus de 500.000 utilisateurs dans plus de 120 pays.