Copper Spinodal Alloys: Part One

Abstract

Ternary copper-nickel-tin (CuNiSn) spinodal alloys represent a breakthrough in metallurgical engineering, delivering larger sizes and engineered shapes with exceptional performance characteristics. These advanced materials combine high strength, excellent tribological properties, and superior corrosion resistance in seawater and acidic environments. Through controlled spinodal decomposition, these alloys achieve a three-fold increase in yield strength compared to base metals. Previously limited to thin sections, new-generation spinodal alloys like Tough Met and Mold Max XL now offer expanded applications in thermal management and structural engineering through innovative processing technologies.

Introduction to Copper-Nickel-Tin Spinodal Alloys

Ternary copper-nickel-tin (CuNiSn) spinodal alloys have emerged as revolutionary materials in modern metallurgy, offering unprecedented combinations of mechanical and physical properties. These specialized alloys deliver larger sizes and engineered shapes while maintaining high strength, excellent tribological characteristics, and exceptional corrosion resistance in challenging environments including seawater and acidic conditions.

Evolution of Spinodal Alloy Technology

Until recently, spinodal copper alloys were commercially available only in thin sections with limited temper options. However, breakthrough developments have led to a new generation of spinodal alloys, including Tough Met and Mold Max XL. These advanced materials have been developed through innovative processing technologies to meet growing demand across diverse thermal management and structural applications.

The development of these highly specialized copper-based spinodal alloys initially focused on bearing applications, particularly for roller cone rock bits. Research revealed that these materials possess specific physical properties that provide significant advantages in producing rock bit friction bearings and similar demanding applications.

Understanding Spinodal Decomposition Mechanisms

Spinodal alloys exhibit a unique anomaly in their phase diagram known as a miscibility gap. Within this narrow temperature range, atomic ordering occurs within the existing crystal lattice structure. The resulting two-phase structure remains stable at temperatures significantly below the gap, creating the foundation for the alloy's exceptional properties.

The processing methodology involves several critical steps. Initially, cast or wrought material undergoes solution heat treatment, allowing partial or complete homogenization and annealing. This is followed by high-speed quenching to preserve the fine grain structure. Subsequently, age-hardening occurs by heating the material to temperatures within the miscibility gap, initiating chemical segregation through spinodal decomposition. This process creates two new phases with similar crystallographic structures but different compositions.

Table 1. Mechanical properties of ToughMet spinodal alloys

| Alloy | Description | Yield Strength Rp0,2 MPa (ksi) |

Tensile Strength Rm MPa (ksi) |

Elengation % | Rockwell hardness |

| UNSC727001 MoldMax XL |

Cast and Spinodally hardenned | 486-690 (70-100) |

562-758 (80-110) |

10-5 | HRc 20-30 |

| UNSC727001 ToughMet3CX |

Cast and Spinodally hardenned | 207-758 (30-110) |

448-827 (65-120) |

45-2 | HRB 62-HRc 32 |

| UNSC727001 ToughMet3AT |

Cast and Spinodally hardenned | 241-827 (35-120) |

482-930 (70-135) |

35-4 | HRB 60-HRc 32 |

Superior Properties and Performance Characteristics

Copper alloys demonstrate exceptionally high electrical and thermal conductivity compared to conventional high-performance ferrous, nickel, and titanium alloys. While traditional copper alloys are typically soft compared to these systems and rarely considered for demanding applications, CuNiSn spinodal alloys successfully combine high hardness with excellent conductivity in both hardened cast and wrought conditions.

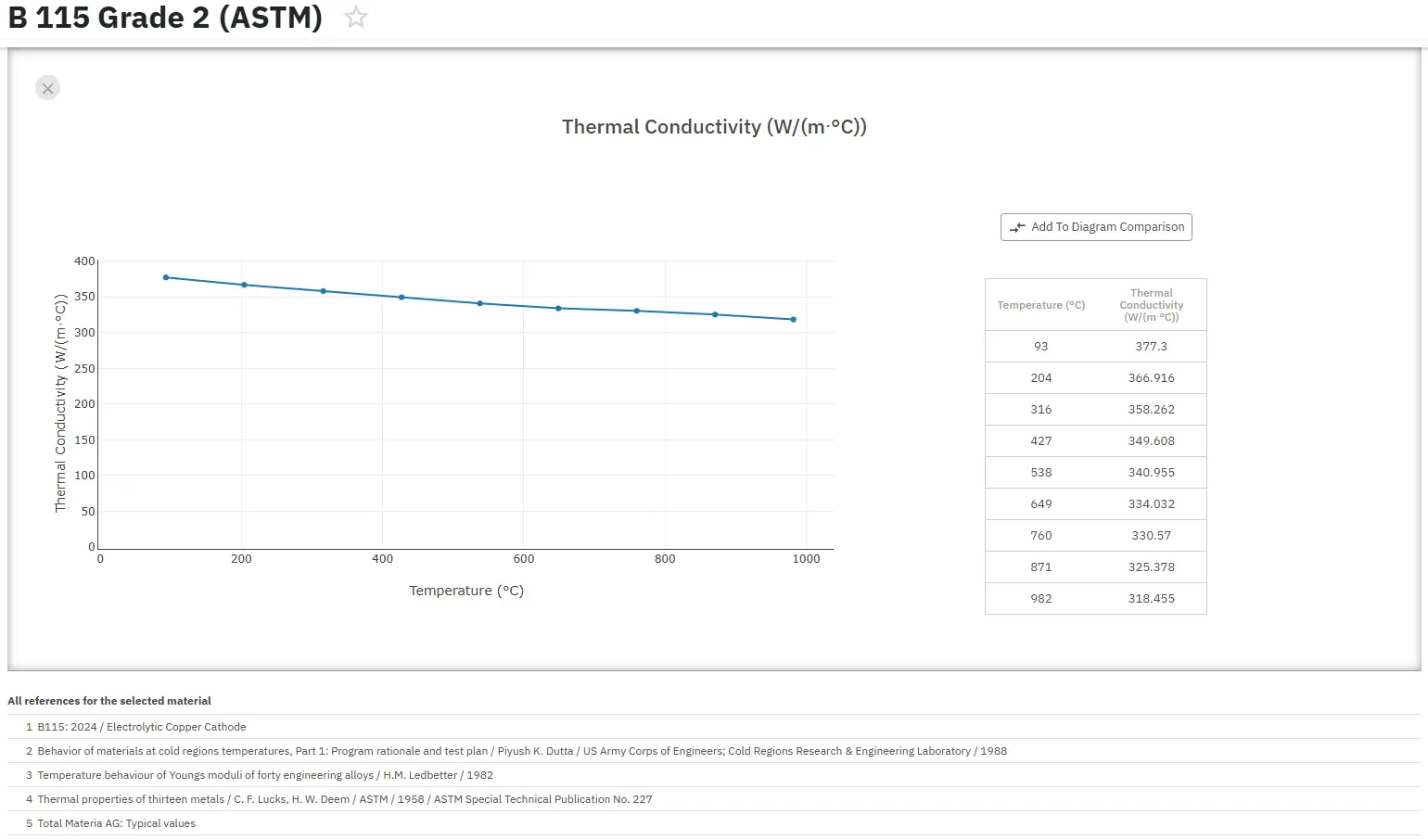

The thermal conductivity of these alloys is three to five times greater than conventional ferrous tool steels, significantly increasing heat removal rates while reducing distortion through more uniform heat dissipation. Equally important is their superior machinability at similar hardnesses, which is five to nine times better than conventional tool steel. These combined properties make spinodal alloys ideal for molds designed for plastic casting applications.

Historical Development and Applications

Copper-nickel-tin spinodal alloys were originally developed by Bell Telephone Laboratories to provide materials with unusually high strength while maintaining long-term resistance to corrosion and erosion in marine and submarine environments. This development addressed critical needs in telecommunications infrastructure exposed to harsh oceanic conditions.

Most copper-base alloys achieve high strength through solid solution hardening, cold working, precipitation hardening, or combinations of these strengthening mechanisms. However, ternary copper-nickel-tin alloys produce high mechanical strength through controlled thermal treatment called spinodal decomposition. Notable examples include Cu-9Ni-6Sn (Brush MoldMax XL) and Cu-15Ni-8Sn (ToughMet 3).

Structural Characteristics and Transformation Process

Spinodal structures consist of fine, homogeneous two-phase mixtures produced when original phases separate under specific temperature and composition conditions, particularly in supersaturated solid solutions of metals with similar atomic sizes. During spinodal decomposition, original phases spontaneously decompose into other phases where crystal structure remains unchanged, but atomic composition differs.

The similarity in atomic sizes ensures that heat-treated spinodal structures retain the same geometry as the original material, preventing part distortion during heat treatment. This characteristic is crucial for precision applications requiring dimensional stability.

Spinodal decomposition occurs when metal atoms in the alloy are nearly identical in size and can form completely homogeneous solid solutions. The term "spinode" derives from the Greek word for "cusp" and was adopted by 19th-century mathematicians to describe functions exhibiting continuous curves with discontinuous derivatives.

Theoretical Foundation and Scientific Principles

Using thermodynamic principles, van der Waals explained the presence of "horizontal cusps" in entropy-versus-volume curves for fluids and identified similar phenomena in other systems. J. Willard Gibbs, the renowned thermodynamicist, utilized free-energy versus composition diagrams to rationalize phase metastability limits in ceramics and alloys, describing the transformation as spinodal decomposition.

The remarkable strength enhancement achieved through spinodal decomposition results in a three-fold increase in yield strength compared to base metals in copper-nickel-tin alloys. This exceptional strength improvement has been attributed to coherency strains produced by uniform dispersions of tin-rich phases within the copper matrix, creating a strengthening mechanism that maintains the material's beneficial thermal and electrical properties.

Читать далее

Доступ к точным свойствам медных сплавов!

Total Materia Horizon содержит информацию о более чем 30 000 медных сплавах: состав, механические, физические и электрические свойства, нелинейные характеристики и многое другое.

Получите бесплатный тестовый аккаунт в Total Materia Horizon и присоединяйтесь к сообществу из более чем 500 000 пользователей из 120+ стран.