Corrosion of Aluminum and Its Alloys: Forms of Corrosion

Abstract

Corrosion is a significant concern in the field of materials science, particularly for aluminum and its alloys, which are widely used due to their lightweight and strength. This article explores the various forms of corrosion affecting aluminum, including atmospheric corrosion, uniform corrosion, galvanic corrosion, and more specialized types such as pitting, crevice, and intergranular corrosion. Aluminum's unique properties, including its ability to form a protective oxide layer, influence its corrosion behavior. The slow degradation process of aluminum often takes years to manifest, making it crucial to understand and identify specific corrosion pathways to implement effective mitigation strategies. This discussion also highlights the chemical reactions involved in aluminum corrosion, emphasizing the importance of environmental factors and alloy composition in determining corrosion susceptibility.

Corrosion Mechanisms of Aluminum

The reaction of aluminum with water is a key factor in its corrosion process, releasing a significant amount of energy:

AI + 3H2O → AI(OH)3 + 3H2 ↑

This reaction illustrates how aluminum can corrode in aqueous environments, leading to the formation of aluminum hydroxide and the release of hydrogen gas. The formation of a protective oxide layer on aluminum surfaces can initially inhibit further corrosion, but various environmental conditions, such as high chloride concentrations or extreme pH levels, can compromise this layer, leading to accelerated degradation. Understanding these mechanisms is critical for developing effective strategies to prevent corrosion and prolong the service life of aluminum structures.

Atmospheric Corrosion

Atmospheric corrosion refers to the degradation of materials exposed to air and its pollutants rather than being submerged in a liquid. This is one of the oldest forms of corrosion and is reported to cause more failures, in terms of both cost and tonnage, than any other environment. Many authors categorize atmospheric corrosion into dry, damp, and wet forms to highlight the different mechanisms of attack based on humidity levels.

The corrosivity of the atmosphere to metals varies significantly by geographic location, influenced by factors such as wind direction, precipitation, temperature changes, urban and industrial pollutants, and proximity to natural water bodies. The design of a structure can also affect its service life, particularly if weather conditions lead to repeated moisture condensation in unsealed crevices or drainage channels.

Uniform Corrosion

Uniform corrosion, or general corrosion, occurs in solutions with either very high or very low pH or at high potentials in electrolytes with elevated chloride concentrations. In acidic (low pH) or alkaline (high pH) environments, aluminum oxide becomes unstable and non-protective.

Galvanic Corrosion

Galvanic corrosion, also known as dissimilar metal corrosion, is one of the most significant economic concerns for aluminum alloys. It occurs when aluminum is electrically connected to a more noble metal while both are in contact with the same electrolyte.

Crevice Corrosion

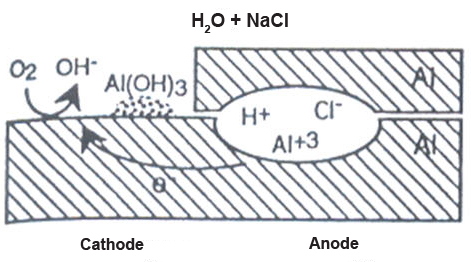

Crevice corrosion requires the presence of a crevice, typically found in saltwater environments, with oxygen available. The crevice can result from the overlap of two parts or a gap between a bolt and a structure. When aluminum is exposed to saltwater, minimal reactions occur initially, but over time, oxygen is consumed within the crevice due to the dissolution and precipitation of aluminum.

Figure 1: Crevice corrosion can occur in a saltwater environment if the crevice becomes deaerated, leading to oxygen reduction reactions outside the crevice mouth. This process can make the crevice more acidic, accelerating corrosion.

Pitting Corrosion

Pitting corrosion occurs in the passive range of aluminum and is characterized by the localized formation of pits. The pitting-potential principle describes the conditions under which metals in a passive state are susceptible to pitting.

Pitting corrosion resembles crevice corrosion. It occurs when the electrolyte contains low levels of chloride anions, and if the alloy is at a potential above the "pitting potential." Pitting typically initiates at surface defects, such as second-phase particles or grain boundaries.

Deposition Corrosion

When designing aluminum and its alloys for corrosion resistance, it is essential to consider that ions from several metals have reduction potentials more cathodic than aluminum's solution potential. These metals can be reduced to their metallic forms by aluminum. Each equivalent of heavy-metal ions reduced results in an equivalent amount of aluminum being oxidized. Even a small reduction of these ions can lead to severe localized corrosion, as the metal deposited can create galvanic cells with aluminum.

Significant heavy metals of concern include copper, lead, mercury, nickel, and tin. Their effects on aluminum are most pronounced in acidic environments; in alkaline solutions, they tend to have much lower solubility and therefore less severe impacts.

Intergranular Corrosion

Intergranular corrosion, also referred to as intercrystalline corrosion, involves selective attack along grain boundaries or closely adjacent regions, with minimal attack on the grains themselves. This term encompasses various forms related to different metallic structures and thermomechanical treatments. Intergranular corrosion arises from potential differences between the grain-boundary regions and adjacent grains.

The anodic path location varies among different alloy systems. In 2xxx series alloys, it appears as a narrow band on either side of the boundary that is depleted in copper; in 5xxx series alloys, it is linked to the anodic constituent Mg2Al3 when it forms a continuous path along a grain boundary. In copper-free 7xxx series alloys, anodic zinc- and magnesium-bearing constituents at grain boundaries are generally responsible. The 6xxx series alloys typically resist this corrosion type, although slight intergranular attack can occur in aggressive environments.

Exfoliation Corrosion

Exfoliation corrosion is a specific form of intergranular corrosion that develops when grains are flattened due to substantial deformation during hot or cold rolling, without subsequent recrystallization. This corrosion is characteristic of the 2000 (Al-Cu), 5000 (Al-Mg), and 7000 (Al-Zn-Mg) series alloys, which exhibit grain boundary precipitation or depleted regions.

To prevent exfoliation in alloy 7075-T6, the newer alloy 7150-T77 can be used as a substitute.

Erosion-Corrosion

Erosion-corrosion of aluminum occurs in high-velocity water, resembling jet-impingement corrosion. It develops slowly in pure water but accelerates at pH levels above 9, particularly in water with high carbonate and silica content.

Though aluminum is stable in neutral water, it can corrode in acidic or alkaline conditions. To mitigate erosion-corrosion, one can alter the water chemistry or reduce water velocity, aiming for a pH below 9 and decreased carbonate and silica levels.

Stress Corrosion Cracking (SCC)

Stress corrosion cracking (SCC) poses a significant challenge for aluminum alloys. SCC requires three simultaneous conditions: a susceptible alloy, a humid or watery environment, and tensile stress that can open and propagate cracks. SCC can manifest in two forms: intergranular stress corrosion cracking (IGSCC), which follows grain boundaries, and transgranular stress corrosion cracking (TGSCC), which traverses through the grains, disregarding grain boundaries.

The trend toward higher strength alloys peaked in the 1950s with alloy 7178-T651 used in the Boeing 707. However, the industry shifted towards lower strength alloys. The yield strength of the upper wing skin did not exceed the 1950 level until the Boeing 777 in the 1990s. Designers opted for lower strength alloys in aircraft like the Boeing 747 and the L-1011 due to better SCC resistance over higher yield strength.

Corrosion Fatigue

Corrosion fatigue can occur when an aluminum structure experiences repeated low-level stress in a corrosive environment. A fatigue crack can initiate and propagate under the influence of the crack-opening stress and the environment. While similar striations may appear on corrosion-fatigued samples, subsequent crevice corrosion in the narrow fatigue crack often obscures them.

Fatigue strengths of aluminum alloys tend to be lower in corrosive environments such as seawater compared to air, particularly in low-stress, long-duration tests. Like SCC, corrosion fatigue necessitates the presence of water but is less influenced by test direction, as fractures from this type of attack are predominantly transgranular.

Filiform Corrosion

Filiform corrosion, also known as wormtrack corrosion, poses a cosmetic issue for painted aluminum. Pinholes or defects in the paint, resulting from scratches or stone bruises, can serve as initiation points for corrosion, particularly with saltwater pitting. Filiform corrosion requires chlorides for initiation and both high humidity and chlorides for propagation.

The propagation is contingent on the alloy's usage. The filament must be initiated by chlorides, progressing similarly to crevice corrosion. The head is acidic, rich in chlorides, and deaerated, acting as the anodic site. Oxygen and water vapor diffuse through the filiform tail, driving the cathodic reaction. Filiform corrosion can be mitigated by sealing defects with paint or wax and maintaining low relative humidity.

Microbiological Induced Corrosion

Microbiological Induced Corrosion (MIC) refers to corrosion exacerbated by biological organisms. A classic example is the growth of fungus at the water/fuel interface in aluminum aircraft fuel tanks. The fungus consumes high-octane fuel, excreting acids that attack and pit the aluminum, leading to leaks. Solutions to this problem include controlling fuel quality and preventing water ingress into the fuel tanks. In cases where quality control is challenging, fungicides may be added to the aircraft fuel.

¡Acceda Ahora a Propiedades de Corrosión Precisas!

Total Materia Horizon contiene información sobre el comportamiento y las propiedades de la corrosión de cientos de miles de materiales para más de 2000 medios.

Obtenga una cuenta de prueba GRATUITA de Total Materia Horizon y únase a nuestra comunidad que traspasa los 500.000 usuarios provenientes de más de 120 países.