Hardenable Alloy Steels

Abstract

Hardenable alloy steels represent the largest tonnage category of alloy steels, typically containing 0.25 to 0.55% carbon content and subjected to quenching and tempering processes for enhanced strength and toughness. These steels incorporate essential alloying elements including manganese, silicon, nickel, chromium, molybdenum, vanadium, aluminum, and boron to optimize properties after heat treatment. The primary advantage of these alloy steels lies in their superior hardenability, which enables the formation of tempered martensite or bainite microstructures in larger sections. This microstructural development results in exceptional toughness and deformation capacity compared to plain carbon steels. The alloying elements function by decreasing austenite transformation rates, permitting slower cooling rates, and enabling specialized heat treatment processes like austempering and martempering for improved mechanical properties.

Introduction to Hardenable Alloy Steels

Hardenable alloy steels constitute the most significant portion of alloy steel production, characterized by carbon content ranging from 0.25 to 0.55% or less. These materials undergo quenching and tempering processes to achieve optimal strength and toughness properties. The incorporation of alloying elements such as manganese, silicon, nickel, chromium, molybdenum, vanadium, aluminum, and boron enhances the properties achievable through heat treatment.

These hardenable alloy steels undergo quench-hardening followed by tempering to achieve the desired strength level for specific applications. Although the final strength level may be comparable to or even lower than what could be achieved through simple cooling from forging or normalizing temperature, the quenching and tempering process is preferred due to engineering and economic considerations.

Microstructural Advantages of Heat-Treated Alloy Steels

The microstructure produced by quenching and tempering hardenable alloy steels, consisting of tempered martensite or bainite, exhibits superior toughness and deformation capacity at any given strength level. Under adverse stress conditions, such as those occurring below a notch in bending applications, tempered martensite demonstrates considerable flow capacity at temperatures where pearlitic steel of equivalent strength would fail in a brittle manner. This enhanced performance is reflected in improved Charpy or Izod impact values.

While plain carbon steels can develop similar favorable microstructures through heat treatment, this capability is limited to small sections. The primary benefit of alloying elements in hardenable alloy steels is enabling the achievement of superior microstructures and accompanying toughness in larger sections.

Hardenability Enhancement Through Alloying Elements

Alloying Elements Dissolved in Austenite

The fundamental effect of elements dissolved in austenite involves decreasing transformation rates at subcritical temperatures. Among common alloying elements, cobalt represents the only exception to this behavior. Since the desired transformation products in hardenable alloy steels are martensite and lower bainite formed at low temperatures, this decreased transformation rate proves essential for successful heat treatment.

This transformation rate reduction enables slower cooling of components or successful quenching of larger sections in a given medium without undesirable transformation to high-temperature products like pearlite or upper bainite. This critical function, known as hardenability, represents the most important effect of alloying elements in these steels.

The hardenability enhancement provided by alloying elements significantly extends the scope of improved properties in hardened and tempered steel to larger sections required in many industrial applications. Common elements dissolved in austenite prior to quenching increase hardenability in the following ascending order: nickel, silicon, manganese, chromium, molybdenum, vanadium, and boron. While aluminum's effect on hardenability has not been precisely evaluated, at 1% Al content used in "nitralloy" steels, the hardenability impact appears relatively modest.

Research has demonstrated that adding several alloying elements in small amounts proves more effective for increasing hardenability than adding larger amounts of one or two elements. For effective hardenability enhancement, alloying elements must remain dissolved in austenite. Steels containing carbide-forming elements such as chromium, molybdenum, and vanadium require special consideration, as these elements exist predominantly in the carbide phase of annealed steels and dissolve only at higher temperatures and more slowly than iron carbide.

Heat Treatment Considerations for Alloy Steels

Quenching Behavior and Challenges

Since hardenable alloy steels often involve relatively large sections and alloying elements generally lower the temperature range for martensite formation, thermal and transformational stresses during quenching tend to be greater than those in smaller plain carbon steel sections. This typically results in increased distortion and cracking risk.

However, alloying elements provide two offsetting advantages. The primary benefit involves permitting lower carbon content for given applications. The hardenability decrease accompanying reduced carbon content can be readily compensated by the hardenability effect of added alloying elements. Lower-carbon steel exhibits significantly reduced susceptibility to quench cracking due to greater plasticity of low-carbon martensite and generally higher martensite formation temperatures.

Quench cracking rarely occurs in steels containing 0.25% carbon or less, with cracking susceptibility increasing progressively with higher carbon content. The secondary function of alloying elements during quenching involves permitting slower cooling rates for given sections due to increased hardenability, thereby reducing thermal gradients and cooling stresses.

Advanced Heat Treatment Processes

The enhanced hardenability of alloy steels enables specialized heat treatment processes such as "austempering" and "martempering," which minimize adverse residual stress levels before tempering. In austempering, components are rapidly cooled to temperatures in the lower bainite region and allowed to transform completely at the chosen temperature. Since this transformation occurs at relatively high temperatures and proceeds slowly, resulting stress levels remain low with minimal distortion.

Martempering involves three stages:

- Rapid surface cooling to temperatures permitting minimal martensite formation

- Temperature equalization throughout the section

- Slow cooling enabling simultaneous transformation throughout the entire section, minimizing transformational stresses, distortion, and cracking risk

Tempering Characteristics and Secondary Hardening

Tempering Behavior of Hardenable Alloy Steels

While hardened steels soften upon reheating, the primary objective of tempering involves increasing the component's capacity for moderate flow without fracture, inevitably accompanied by strength reduction. Since tensile strength closely correlates with hardness in heat-treated steels, monitoring tempering effects through Brinell or Rockwell hardness measurements proves satisfactory.

Figure 1: Statistical relationship between Brinell hardness, tensile strength, and yield strength

Figures 2-4: Softening patterns of nine 0.45% C steels with increasing tempering temperature

Figure 5: Effect of carbon content on softening pattern in terms of Rockwell C hardness

The softening pattern of similar steels with carbon content ranging from 0.25 to 0.55% can be estimated using the provided figures. Carbon content effects on tempered steel hardness are more pronounced at lower tempering temperatures than at 1200°F (649°C) and higher, with effects decreasing beyond 0.50% carbon content.

Secondary Hardening Phenomenon

Alloying elements generally retard softening rates, requiring higher tempering temperatures to achieve given hardness levels compared to carbon steels of equivalent carbon content. Individual elements demonstrate significant differences in their retarding effects. Nickel, silicon, aluminum, and manganese, which have minimal carbide-forming tendency and remain dissolved in ferrite, show only minor effects on tempered steel hardness.

Chromium, molybdenum, and vanadium, which migrate to the carbide phase when diffusion permits, significantly retard softening, particularly at higher tempering temperatures. These elements create discontinuous softening behavior, with some temperature ranges showing retarded softening or actual hardness increases with rising tempering temperature. This characteristic behavior, known as "secondary hardening," results from delayed precipitation of fine alloy carbides.

Conclusion

Hardenable alloy steels represent a critical category of engineering materials that combine optimal strength, toughness, and processability through carefully controlled alloying and heat treatment. The strategic incorporation of alloying elements enhances hardenability, enabling superior microstructural development in larger sections while providing flexibility in heat treatment processes. Understanding the complex interactions between composition, processing, and properties remains essential for successful application of these versatile materials in demanding engineering applications.

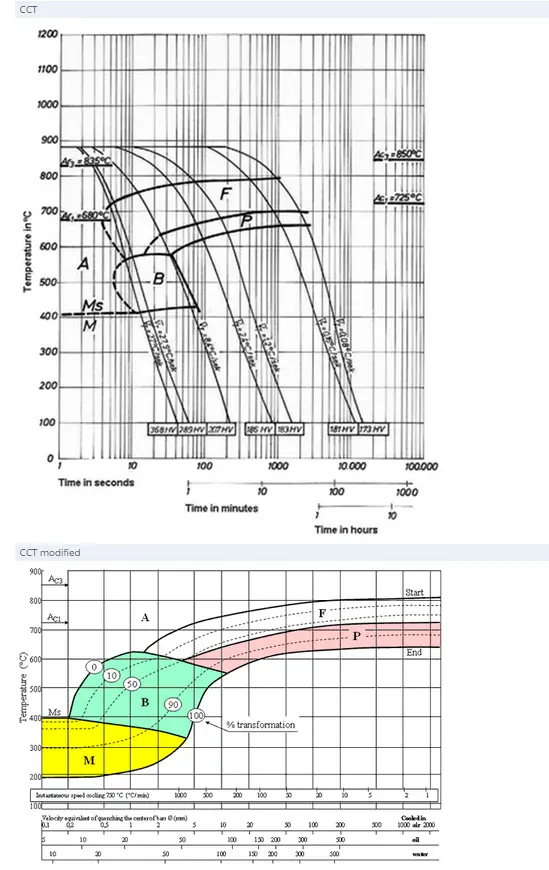

立即查看数万种材料的热处理曲线!

Total Materia Horizon 包含上数万种材料的热处理细节、淬透性曲线、硬度回火曲线、TTT 曲线和 CCT 曲线 等。

申请 Total Materia Horizon免费试用帐户,加入来自全球 120 多个国家超过 500,000 名用户的大家庭。